It’s an auspicious moment for retrocomputing fans, as it’s now four decades since the launch of the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. This budget British microcomputer was never the best of the bunch, but its runaway success and consequent huge software library made it the home computer to own in the UK. Here in 2022 it may live on only in 1980s nostalgia, but its legacy extends far beyond that as it provided an entire generation of tech-inclined youngsters with an affordable tool that would get them started on a lifetime of computing.

What Was 1982 Really Like?

There’s a popular meme among retro enthusiasts that the 1980s was a riot of colour, pixel artwork, synth music, and kitschy design. The reality was of growing up amid the shabby remnants of the 1970s with occasional glimpses of an exciting ’80s future. This was especially true for a tech-inclined early teen, as at the start of 1982 the home computer market had not yet reached its full mass-market potential. There were plenty of machines on offer but the exciting ones were the sole preserve of adults or kids with rich parents. Budget machines such as Sinclair’s ZX81 could give a taste of what was possible, but their technical limitations would soon become obvious to the experimenter.

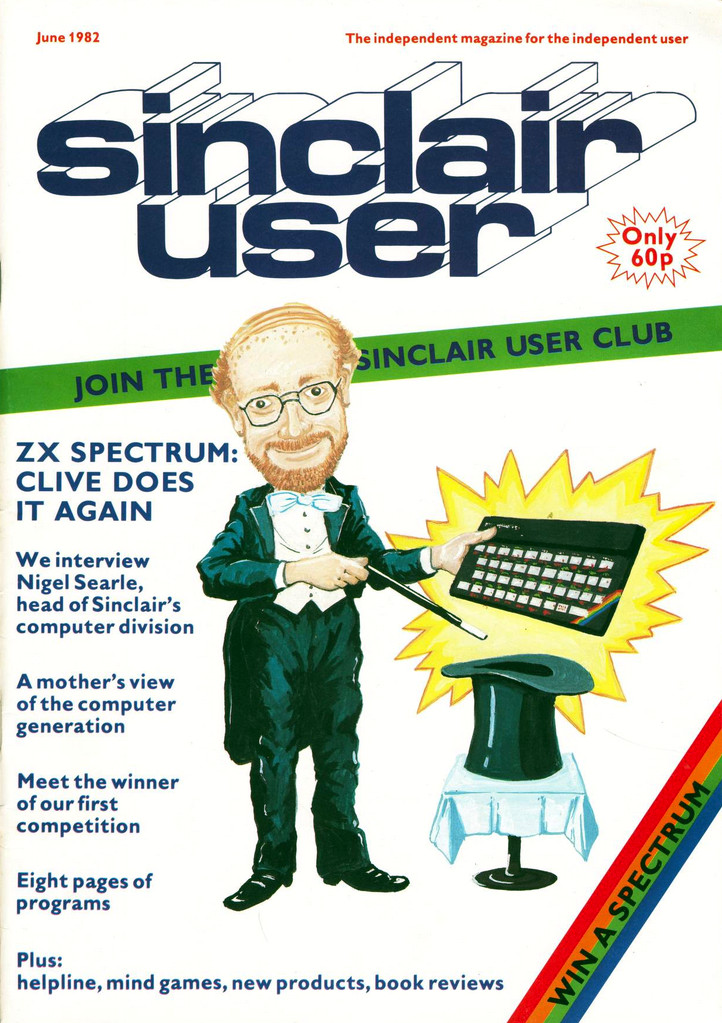

1982 was going to change all that, with great excitement surrounding three machines. Here in the UK, the Acorn BBC Micro had been launched in December ’81, the Commodore 64 at the start of ’82, and here was Sinclair coming along with their answer in the form of first the rumour of a ZX82, and then the reality in the form of the Spectrum.

This new breed of machines all had a respectable quantity of memory, high-res (for the time!) colour graphics, and most importantly, sound. The BBC Micro was destined to be the school computer of choice and the 64 was the one everybody wanted, but the Spectrum was the machine you could reasonably expect to get if you managed to persuade your parents how educational it was going to be, because it was the cheapest at £125 (£470 in today’s money, or about $615).

Never Quite As Good As Its Competitors, But Cheaper

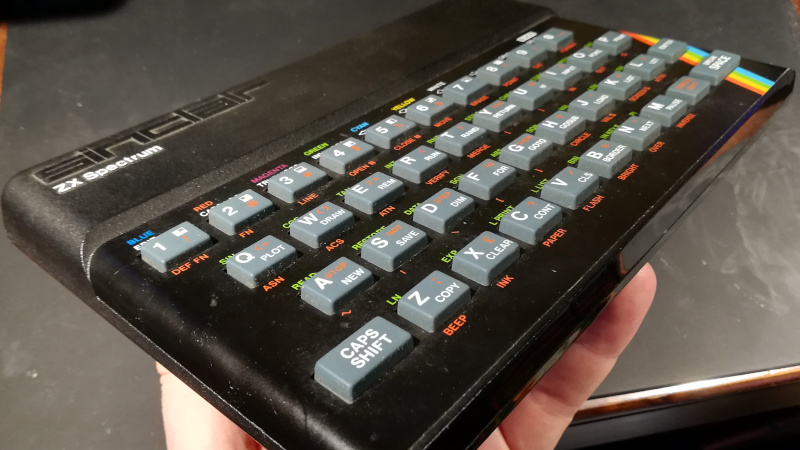

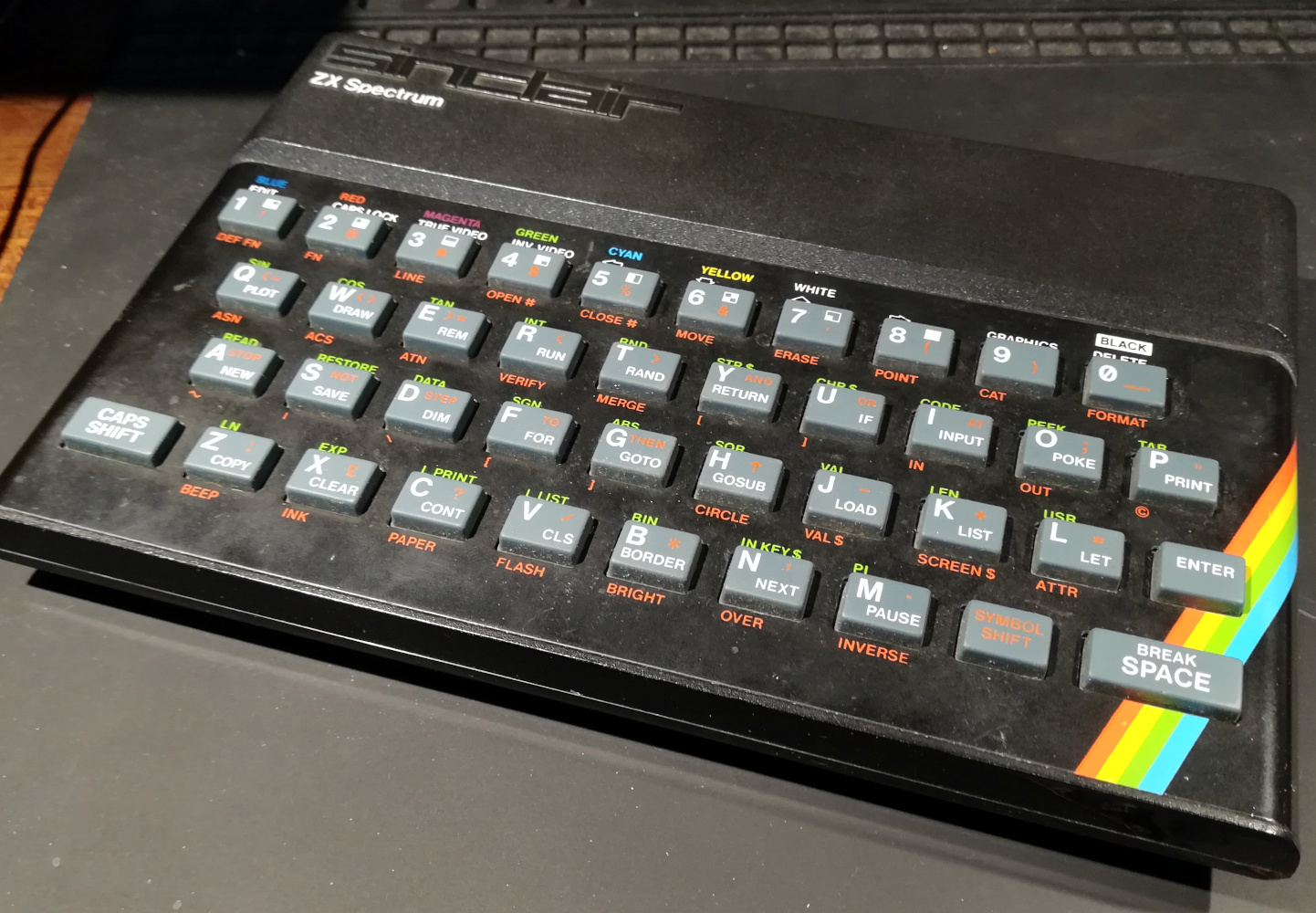

For a teen in 1982 the Spectrum was an incredibly big deal, but from 2022 how did it rack up? It’s very obviously a development of their earlier ZX81, with an updated version of the same Sinclair BASIC and the same single-key keyword entry system. The design came from Rick Dickinson, the same industrial designer who had shaped the ’81, and for the Spectrum there was a new keyboard that topped the underlying membrane with a squishy rubber moulding.

With a 3.5 MHz Z80 it could compete in the processing stakes, but its architecture and memory management model was very similar to that of its predecessor. An improved logic design in its Ferranti ULA now freed the processor up from drawing scan lines, so there was no longer a FAST mode in which the display went blank, and the full power of the processor could be used at all times. The original Spectrum came with 16 MB of memory upgradeable to 48 kB via an internal daughterboard, but these early models were soon supplanted by a 48k-only model that became the huge-selling version.

The high-resolution graphics came in at 256 x 192 pixels which was a great improvement over the block graphics of the ZX81, but the attribute-based colour system operated on a much lower resolution and gave an effect of blocks of colour. Clever software designers could mask this as much as possible by arranging their tiles to coincide with the blocks, but sometimes this effect could be seen in even the most polished of titles. The Acorn and Commodore both had far better graphical capabilities, but the Sinclair was good enough for its teenage audience to forgive it. (As an aside, clever ZX81 hackers eventually figured out how to make it too do high-res without an add-on, but this came too late to make a splash).

It’s fair to say that the sound capabilities of the first generation of Spectrums was disappointing, being simply a speaker connected to a bit on an I/O port that could make beeps or even poor quality PWM with some very clever programming, but couldn’t be described as competing with other machines that had dedicated sound chips. Later machines rectified this situation, but we’re concerned here only with the original.

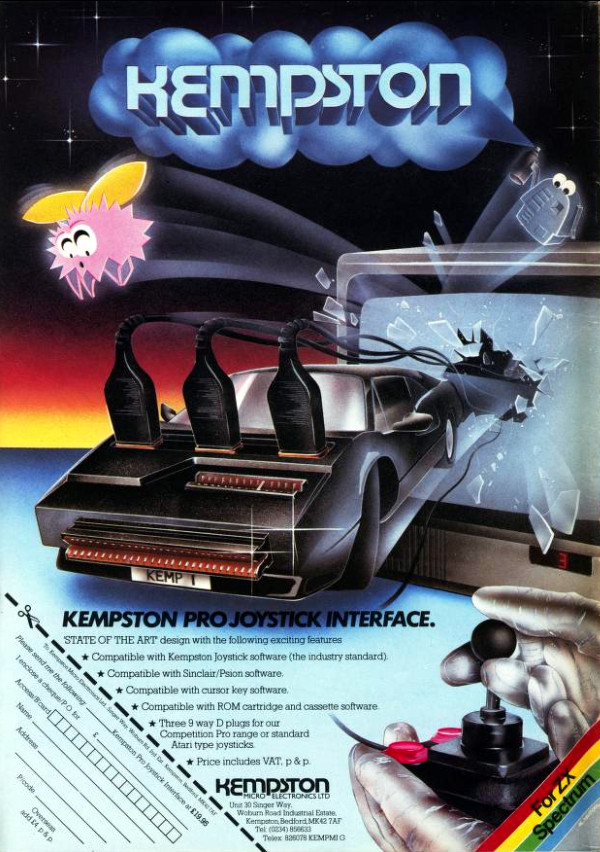

Beyond the hardware described, the Spectrum had very little else built-in. Storage was via tapes as was the case with most computers of the day, and with none of the Commodore or Acorn’s array of ports it simply exposed the Z80 signals to an edge connector at the rear. Sinclair themselves produced a thermal printer add-on as well as interfaces that gave access to joysticks, serial ports, simple networking, and of course their Microdrive tape loop storage peripheral. The interface that the majority of owners would have had though came not from Sinclair, the Kempston joystick interface was an essential for any owner.

So the Spectrum was a huge success for its attractive price, despite being in the best tradition of Sinclair products a device that promised much while delivering less than its competitors. It soon spawned a healthy ecosystem of magazines and third party companies supplying every conceivable upgrade or piece of software, and geeky 1980s teens throughout the land would arm themselves for playground arguments over the relative merits of a Z80 versus a 6502. Having been a ZX81 owner I joined the party a little later, and I credit the Sinclair machines with teaching me the fundamentals of how a microcomputer works in a way that no machine I’ve owned since could come close.

The Spectrum, Viewed From 2022

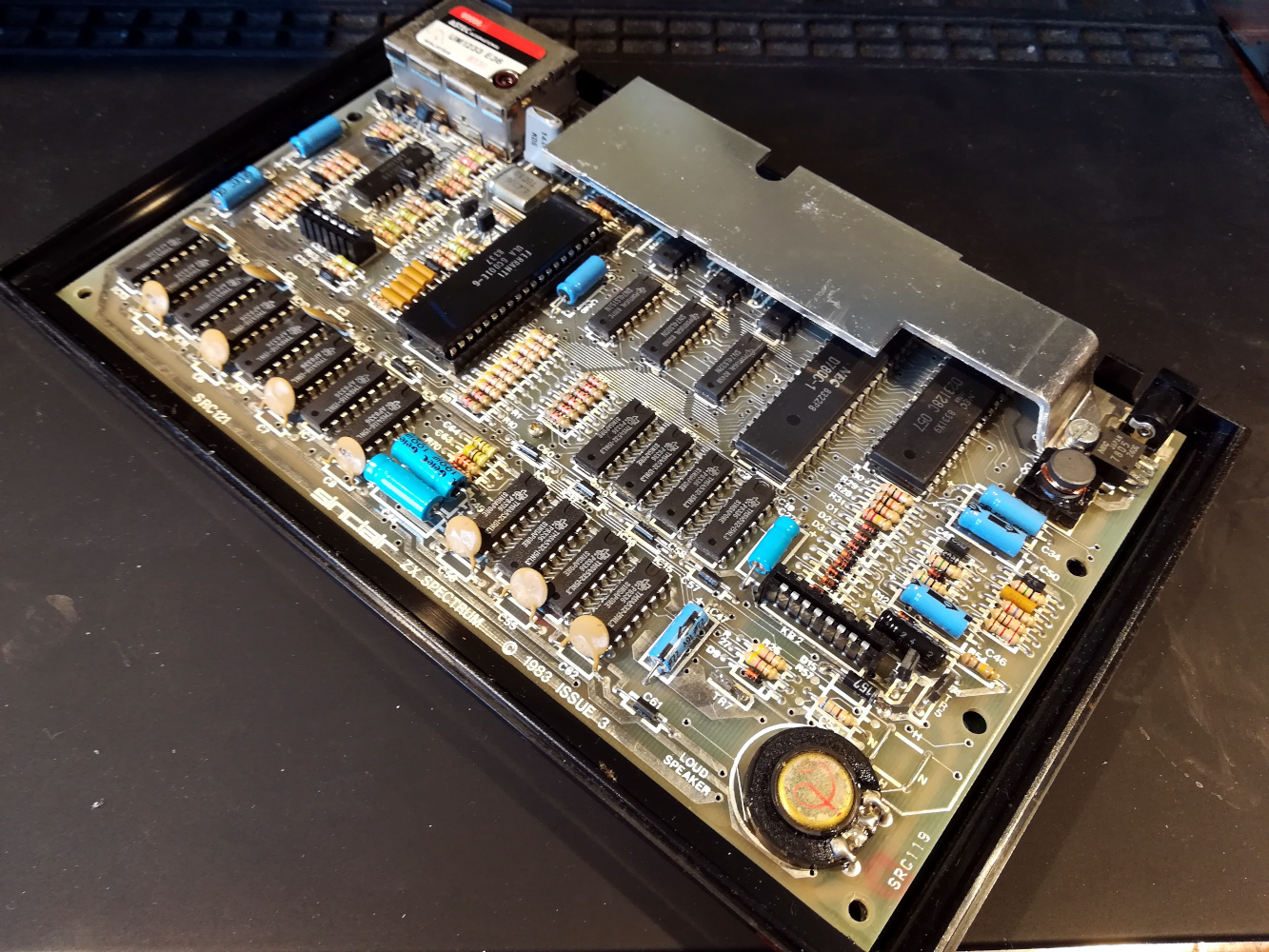

After a little looking through storage boxes, I’ve pulled out my box of all things Sinclair for this article. It contains my Spectrum alongside the ZX81, as well as a pile of cassettes and peripherals. My model is an Issue 3, 48 kB version made in 1983, and is from the moment when a Spectrum was the machine to have. Opening it up reveals the PCB below the keyboard, with the Z80, ROM, ULA, and RAM as well as the video modulator in its silver can. As Sinclair products went, this was a pretty reliable one, and though I really should replace its ageing capacitors, it still works. I’m not sure I have the patience to get back into Sinclair Basic or Z80 machine code again on real hardware, but that box contains a lot of memories.

For me the Spectrum will always be the classic rubber-keyboard model, but as the 1980s wore on and I drifted further into amateur radio and eventually back into 16-bit computers, the little Sinclair continued to evolve. A “Plus” model followed with a better keyboard and styling similar to the company’s QL 16-bit offering, and then a 128 kB bank-switched model with extra capabilities including a proper sound chip. By then the commercial failure of the QL was dragging the company to the brink, and eventually in 1986 the entire Sinclair computer range was sold to their competitor Amstrad. The Amstrad Spectrums would gain extra capabilities including built-in cassette and disk drives as well as the ability to run CP/M, and I am astounded to find that they continued to be made until 1992.

Everyone who got their technological start through that era of home computers sees “their” machine as the “classic” platform against which all must be measured, and while I may be no exception I am certainly not overlooking its flaws. It was a budget machine with limited on-board capabilities compared to its competitors and requiring extra peripherals to do almost anything not possible with the keyboard, but its value lies in what it gave to the lucky teens who received one for Christmas back in 1982.

Most of them would have used it for games, but in any school there was always a hard core of kids who ran with it, and as one of those kids in my school I am thankful for what it game me and many of my colleagues since. I would never have been able to save up £350 for a BBC Micro and my parents certainly wouldn’t have been able to buy me one, but because Sinclair were providing something I could save up for, I could use mine to gather skills I still use today.

Now that’s an educational computer!