[ comments ]

Table of Contents

- Preface

- DAW GUIs are complicated

- My views on the Rust GUI landscape

- What actually makes a GUI "high performance"?

- My views on the Rust GUI landscape - Part 2

- Potential plans moving forward

- Should I stick with Rust?

- Options using native Rust libraries

- Options using Rust bindings

- Options using C++

- Development plan?

- Final thoughts

Preface

I would like to write about where my head's been the past several months. If you've noticed that Meadowlark's development has slowed down, this article explains why.

Essentially I've really underestimated how difficult it would be to develop the frontend/GUI of Meadowlark. Not just with how complicated a DAW's GUI is, but also in finding a GUI library that is actually suitable for the task.

I want to use this blog post to do three things. First I want to highlight why this is such a hard problem. Second I want to share my thoughts on the current state of Rust's GUI library ecosystem. And third I want to share some potential paths I can take for the future of Meadowlark.

I would like to hear any thoughts people may have (especially on the part on potential paths for this project). I am most active in my Discord server if you are interested in discussion.

DAW GUIs are complicated

Saying that Meadowlark's frontend/GUI has unusual needs (both performance needs and just features in general) is an understatement. DAWs might just have one of the most complicated GUIs out of any piece of software out there.

Here are some complications I've come across, divided into three parts.

Performance problems

- DAWs have a lot of toolbars and panels (browser panel, timeline panel, piano roll panel, fx rack panel, mixer panel, audio editor panel, automation editor panel, settings panel, etc.).

- Some widgets like decibel meters and other visualizers are constantly being animated, meaning the GUI library needs to efficiently redraw the screen every frame.

- In addition, visualizers can be expensive to render on the CPU (especially spectrograms/spectrometers). Ideally you should use custom shaders to render them on the GPU.

- Clips on the timeline are notoriously expensive to render. There needs to be some way to cache the contents of clips into a texture (Either directly or by making use of the GUI library's "damage tracking" which I'll get into later.)

- Audio clips are the biggest culprit, because rendering waveforms requires the CPU to first do a linear search through the source material for peak values, and then render the waveform pixel-by-pixel (or even better use custom shaders to send commands to the GPU).

- Automation clips can contain a bunch of bezier curves, which are slow to render.

- Piano roll clips can contain lots of little rectangles in order to display a "minimap" of the MIDI notes inside of it.

- On top of all this, clips can contain text labels which can also be expensive to render.

- The fact that a timeline is zoom-able also makes it harder to cache the rendering of clips. If the timeline changed its zoom level, all visible clips pretty much have to redraw all of their contents.

- Piano rolls can also be expensive to render if there is a bunch of MIDI notes, especially if there are text labels on the notes.

- If the user clicks on a folder in a sample browser containing hundreds or even thousands of files, allocating a label widget for each file in the browser list will be very expensive. Something like the list factory in GTK is needed here.

- We want to reserve as much CPU as possible for the actual audio processing. Ideally the GUI shouldn't take up more than one or two CPU threads.

- On some platforms, we also need to make sure there's actually enough CPU left for 3rd-party plugins to render their GUIs.

GUI library problems

- DAWs have unconventional widgets and layouts. For example, not only does a mixer track contain custom widgets like knobs, sliders, and decibel meters, but all of those widgets are not positioned according to a traditional layout scheme like a list, grid, or a tree.

- This is especially true if the DAW has a horizontal FX rack like I plan with Meadowlark.

- DAWs don't follow traditional/recommended design standards or "human interface guidelines". They have a bunch of custom styling to cram all of that information onto the screen (and to actually look like an audio application).

- This custom styling and layout also makes it harder to support localization.

- Ideally I want to support loading user-generated themes.

- Preferably the DAW should let the user pop out panels into another window (or at least support a preset number of multi-window workspaces). Multi-window setups are harder to deal with in code.

- The timeline and piano roll are not simple "scroll areas". They can be zoomed in and out, meaning there needs to be some kind of custom positioning and sizing logic for clips and MIDI notes.

- When the timeline is zoomed in very far and/or a clip is very long, the resulting width of the clip in pixels can be very, very long. This could cause issues if the UI library tries to render the whole thing (especially if the clip has expensive contents). So you need to make sure only the visible part of the clip is actually processed and rendered.

- In order to deal with really long audio clips, you need to stream the file from disk. This makes rendering their contents on the timeline much more complicated because now you are dealing with an async operation.

- Some widgets like knobs and sliders need to be able to listen to raw mouse input data as opposed to absolute mouse coordinates (or even better is the ability to use pointer locking). Otherwise if the user's mouse hits the edge of a screen or moves outside the window while dragging one of these widgets, they will stop working.

- This is especially true with a horizontal FX rack where there are bunch of knobs and sliders near the bottom of the screen.

- There needs to be some way to easily input the value of a knob/slider parameter using a keyboard. Ideally in some sort-of pop-up text input box.

- There needs to be extensive support for custom keyboard shortcuts. This includes shortcuts that could potentially conflict with accessibility features such as using the spacebar to start/stop the transport.

- In addition, the UI library needs to support keyboard shortcuts even when a widget/window isn't focused. For example pressing spacebar to start/stop the transport while inside a 3rd-party plugin window.

- There needs to be some way to access the raw window handles in order to host 3rd-party plugin GUIs.

Complicated logic

- There are three separate states that must be kept in sync: The state of the save file (which I call the "source state"), the state of the GUI, and the state of the backend. These have to be separate states because:

- The source state, the backend, and the GUI sometimes want different units. For example, the start of an audio clip on the timeline may be in units of beats in the source state, units of samples in the backend, and units of pixels in the GUI. So units must somehow be efficiently converted from the source state the the backend/GUI state.

- The backend process runs on a realtime thread, so you cannot just use simple mutexes to read the source state. Some other method must be used like lock-free message channels or garbage-collected clone-on-write smart pointers.

- There are situations where the state of the GUI/backend can be different from the source state. For example when the user is in the process of dragging the position of a clip on the timeline, the clip needs to move in the GUI, but the change shouldn't actually be committed into the source state or backend state until the user lets go of the mouse button. Otherwise it would cause expensive updates to happen every single frame the user is dragging the clip.

- Another example is when the backend can't find a plugin listed in the source state. In this case, both the backend and the GUI will have a "missing plugin" placeholder. But this shouldn't cause the original state of the plugin to be overwritten.

- There can be a lot of drag-and-drop targets which can be complicated to implement. For example:

- dragging samples/midi/automation from the browser onto the timeline

- dragging samples/midi/automation from the browser onto a track header to add it to the timeline

- dragging samples/midi/automation from the browser into an empty portion of the timeline to add a new track

- dragging samples/presets from the browser onto a plugin in the horizontal FX rack

- dragging a modulation source onto a parameter in the horizontal FX rack

- dragging a plugin in the horizontal FX rack into a slot in a container device

- dragging a plugin in the horizontal FX rack between two other plugins to reorder them

- dragging a plugin from the horizontal FX rack onto a track header to move that plugin to that track

- dragging a track header/mixer track into an area between two other tracks to reorder them

- dragging a clip/multiple clips onto a different lane to move them to another track

- The code to interact with the timeline can be very complicated because of all the different operations you can perform. For example:

- panning/scrolling the timeline (horizontally and vertically)

- zooming the timeline

- clicking to set the position of the playhead

- clicking/dragging to set the position of the loop points

- adding/removing/dragging time markers

- adding/removing/resizing/reordering tracks/lanes

- using the pencil tool to draw new clips onto the timeline

- selecting multiple clips with Ctrl+Click or the lasso tool

- dragging one/multiple clips horizontally to change their position (and snapping their positions to the grid unless Shift is held down)

- using the arrow keys to nudge the position of one/multiple clips

- dragging the edge of one/multiple clips to change their lengths

- dragging a handle on an audio clip to adjust the crossfade

- adding/removing nodes on an automation clip

- using the lasso tool to select multiple nodes on an automation clip

- dragging one/multiple nodes on an automation clips (and snapping their positions to the grid unless Shift is held down)

- adjusting the curvature between nodes on an automation clip

- slicing a clip

- copy/pasting single/multiple clips (and possibly on a different track)

- duplicating clips (and making sure they are grid-aligned)

- dragging one/multiple clips up/down to change the track they are on

- reversing/stretching/pitch-shifting and audio clip

- audio clips can have even more complicated maneuvers such as time stretching just a selected portion of a clip in order to correct the timing of a recorded performance

- dragging an audio file/automation clip/MIDI clip from the browser onto the timeline

- Undo/Redo logic can get complicated:

- Like I mentioned above, there are a lot of operations that can be done with tracks, clips, MIDI notes, plugins, etc.

- The undo/redo operations need to perform as expected when manipulating multiple items at the same time. For example, if you select and bunch of clips and drag their positions, hitting the undo button should move back all of those clips at once and not one at a time.

- Not all operations are undo-able, especially operations dealing with 3rd-party plugins since plugins are in charge of their own state, not the host.

- There are some more complexities when it comes to hosting 3rd-party plugin windows which I won't get into here.

My views on the Rust GUI landscape

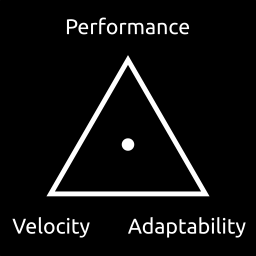

This video I watched recently brings up a good point about software development (Albeit the video is bit heavy-handed with its message and I might be taking the original message a bit out of context, but I think the point still stands). In the video, there is this chart:

Here are what each each of the ends of the triangle mean:

- "Performance" literally means how well the application performs.

- "Velocity" means how fast an application gets developed. For example, did the app take a few weeks to develop, or several months?

- "Adaptability" means how easily features can be changed/added/removed from the application in the future (another good word for this is "maintainability").

The idea of this chart is that you can't have all three:

- If you focus too much on performance, it will take much longer to actually create the app and it will be harder to change/add/remove features in the future.

- If you focus too much on adaptability, you are potentially over-engineering and over-abstracting your code architecture to the point where it both hurts performance and it eats into the time actually developing the app.

- If you focus too much on velocity (as in taking a quick n' dirty path to get something out as fast as possible), not only will the application be unoptimized, but it will be harder to actually fix any problems you have in the future, possibly requiring you to rewrite the code later.

Now this brings me to my current views on Rust GUI libraries (and other modern GUI libraries in general, not just Rust). It is my observation that modern GUI toolkits tend to focus too hard on the velocity/adaptability end of the triangle and not the performance end.

Now I totally get why this is. Every developer wants to have a GUI library that is easy to use and gives results quickly. Every developer wants a GUI that is not a nightmare to maintain. And the clever architecture of Rust GUI libraries definitely delivers on those fronts (and at a level that has probably not been done before).

However, I think Rust GUI libraries seriously mistake and/or neglect what it actually takes to have a GUI that has good performance when scaled up to a large project. Of course large and complicated GUIs may not be a target use-case for some or all of these libraries. My point is more to highlight why they won't quite work for Meadowlark.

Now first I should mention that I am definitely aware of premature optimizations, and I am aware that I'm stressing a lot about performance before actually creating the GUI. However, that's not what I'm worried about. What I'm worried about is the GUI library I end up using not even allowing me to do optimizations in the first place if I needed to (and I will very likely need to).

So to start, I should explain what it actually takes for a GUI to be "high performance".

What actually makes a GUI "high performance"?

Rendering performance

The first aspect that makes a "high performance" GUI is quickly rendering the contents onto the screen. While this has definitely gotten easier in the modern age of GPU-acceleration, I don't believe GPU-acceleration alone is a silver bullet:

- The CPU still has to package all of the commands into a buffer to send to the GPU. If there are thousands of UI elements on the screen, that is a lot of commands for the CPU to package (especially when using OpenGL).

- Text looks awful when rendered on the GPU. This is just due to the nature of how complex text rendering is. Best case is to have the CPU render each glyph into a texture atlas, and then have the GPU sample each glyph one at a time from this atlas. Even then, this approach has its footguns.

- GPU power is not free. Having the GPU render all of those elements on all of those pixels every frame can chug a lot of battery. GPUs are more optimized for dealing with triangles and textures, and not so much for dealing with vector graphics. While consuming a lot of GPU power is fine for a video game, it's not as fine when it's an app meant to open for hours at a time.

So I believe it's still important to do what's called "damage tracking", where only the widgets that have changed get redrawn. This is usually done by clearing a rectangular region around a widget, filling the background back into that cleared region, and then redrawing the widget. Though this does definitely get complicated when the "background" is not a flat color, but is instead a hierarchy of other (possibly partially-transparent) widgets.

I also learned recently that damage tracking is not just an optimization on the application-level, but on the operating system level as well. Every OS has some sort of "damage region" concept built into the OS's compositor system, which allows the OS to more efficiently blit small rectangles onto the final screen output instead of needing to blit the entire application's window onto the final output.

That being said, this OS-level optimization is probably not as necessary in the modern age since GPUs are pretty efficient at blitting large textures together.

Input handling performance

The second aspect is efficiently handling input events. If a GUI library sends every mouse/keyboard/animation event to every widget, then that can get really expensive when there are a bunch of nodes in the widget tree.

Iterating a tree structure is not the most efficient to begin with. But there is a bigger problem called "pointer chasing", which happens when you try to excessively dereference a bunch of pointers at once (in this case we dereference each node/widget pointer in order to call its on_event() method).

A good first step is to only send events to the widgets that actually ask for it (although a lot of widgets want both mouse and keyboard input). Mouse input can be optimized by skipping all child nodes if the cursor isn't contained within the bounds of the parent node (however, you then need a system to handle drag operations since those can happen outside the bounds of the widget being dragged).

Update handling performance

The third aspect is efficiently updating the widget tree. When an input event causes a widget to change, the GUI system needs to not only tell the rendering system that the widget has changed and it should be re-rendered, but it also needs to check if any other widgets have changed as a side effect. For example, if the width of a widget changed, that could cause the position of other widgets next to it to change.

My views on the Rust GUI landscape - Part 2

In my experience, every Rust GUI library fails in one or more of those categories listed in the section above.

But I don't believe this to be due to the developer's lack of caring or lack of skill. I think this is an issue rooted in the very architecture that Rust GUI libraries tend to use.

I have found that Rust GUI library architectures (and a lot of modern GUI architectures in general, not just Rust) tend to fall into three categories.

The web-based toolkits

The first category is web-based GUI solutions such as electron and tauri. I understand why these solutions are so popular, it's because they fall square into the "velocity" corner of the triangle. Do you know HTML/CSS or have employees that do? Congratulations, you can create desktop apps!

However, it's no secret that I'm quite against this industry trend of "let's use web tech for everything!":

- Both Javascript and the DOM are slow, there's no changing that. Webassembly is definitely a good step forward, however that still doesn't fix the DOM problem.

- Web engines are also expensive in terms of memory. Not just RAM, but also in terms of file size (especially apps built with electron). I'm sure a lot of users are tired of every app having a minimum size of around 50-100MB.

- Both Javascript and the DOM model make it harder to create maintainable codebases using things like abstractions (thus it's not very "adaptable"). Again webassembly helps here, but the root problem is still there.

- It takes resources away from the much-needed innovation in native GUI toolkits.

- On a slightly political note, web tech is all but dominated by Chromium (and therefore Google). Using web tech for everything gives Google a lot more power over the software industry as a whole, and it should be obvious why this is potentially a bad thing.

The immediate-mode toolkits

The second category is immediate-mode GUI solutions such as egui, imgui, and makepad. This architecture is both very quick and easy to use, while also having a high degree of adaptability due to the fact that "the GUI is a function of the data".

However, this is definitely at the cost of performance. Whenever any part of the data changes, it reconstructs/restyles/relayouts the entire widget tree and redraws the entire screen widget-by-widget. While there can be some clever caching optimizations under the hood, the architecture is still flawed in this regard. This performance is not a problem if the app is small or the app already redraws every frame like a video game. But it is a problem when the GUI is as complicated as a DAW GUI.

The Elm-based toolkits

An architecture that is very popular in the Rust ecosystem is the Elm architecture (or some variation of the architecture). This is because it gets around the problem of shared mutability in Rust, while also having a very high degree of adaptability/maintainability due to its data/event-driven nature. GUI toolkits that use a variant of this architecture include Iced, Vizia, Druid Relm, and even Apple's SwiftUI to some extent.

However, the Elm architecture still has drawbacks in terms of performance. While performance is definitely better than immediate-mode (because they are what is called "retained-mode"), these kind of architectures still do a lot of work in order to detect changes to the state of the application. This is mainly to do with their data-driven nature. Because any part of the widget tree can depend on any part of the input data (this input data also includes things like layout and styling), the GUI library has to somehow check the entire input data and the entire widget tree for changes. Each library has a different method for doing this, with varying levels of performance.

Still, I should mention that the alternative to a data-driven approach is to have the user manually update the widget tree themselves. This is definitely more time consuming and more error-prone, so I understand why the industry is gravitating away from it. And I don't dislike the concept. In theory it has the potential to have "good enough" performance at a large scale (of course the actual real-world performance is a different question).

However, there's a much bigger problem with these Rust GUI libraries in particular, which is that none of them actually do any kind of damage tracking for rendering. They redraw the whole screen widget-by-widget every frame, relying heavily on GPU-acceleration in order to make performance not turn into a slideshow. (Although this situation might change for one library which I'll get into later.)

Potential plans moving forward

So all this brings me to my current situation of figuring out the best path forward for Meadowlark. This is the part where I would like to hear your thoughts if you have any.

I think there are three main questions to answer here: Should I stick with Rust for Meadowlark's frontend, what GUI library should I use, and what method is best to actually go about developing the frontend?

Should I stick with Rust?

This first question is definitely a tough one. Meadowlark has been rooted in Rust since the beginning (even starting out as the "Rusty DAW project").

However, from my experience I'm just not sure anymore that the Rust GUI ecosystem is quite there yet (or even that it will be "there" in a year or two). GUI is just so complicated that I'm not sure that passion-driven projects alone are enough to push it to the level of mature C++ libraries. And frankly, I find it harder to get motivated to work on Meadowlark when the underlying technology is unproven and experimental.

But on the flip side, maybe my concerns are unwarranted and Rust is still the best way to go? I don't know. Either way, I'll list the potential options there are for both Rust and C++ to get a better idea on answering this question:

To be clear, with whatever path I choose, I still want to use Rust for the backend as much as possible (namely in my dropseed engine).

It is possible to use both C++ and Rust in the same project thanks to cxx. Of course it will make building more cumbersome, but it's a tradeoff to consider.

Options using native Rust libraries

Here are the native-Rust options I think have any potential to fit my use case.

Vizia

I've used Vizia for the latest attempt at Meadowlark's GUI. It still has potential and I may still decide to stick with it, but I do have quite a few concerns with it.

Pros

- Creating the non-timeline portions of the GUI was a breeze with this library.

- I am close with the developer on Discord, and he has expressed interest in adapting Vizia to cover the needs of Meadowlark.

Cons

- Vizia's performance is currently quite poor. It currently excessively iterates the widget tree to search for changes, and it redraws the whole screen on every change. While various optimizations are on the roadmap (including a form of damage-tracking), a part of me is still concerned with how well it will turn out in practice.

- The data-binding system has proven to be a bit awkward when the application state is very complicated. In order to make it work, I need to create a "GUI state" that is separate from my source state, which means that I still need to manually keep this GUI state in sync with my source state. So for my use case, I've found there is not much benefit to the data-binding system over just being able to manually update the widget tree.

- It's declarative architecture makes it difficult to put wildly different widgets into a list. Namely a horizontal list of inline plugin GUIs on the horizontal FX rack.

- There is currently a noticeable amount of input latency when using vsync. This could just be the nature of femtovg or even just OpenGL in general, but it would be a bummer if it could never be fixed.

- Vizia is still missing a lot of features I need such as multi-window support, custom shaders, global keyboard shortcuts, localization features, list factories for long lists of items, and pointer locking. Again, these are on the roadmap, but that leads me to my last concern:

- Vizia is mainly worked on by just one person, and there is no funding behind it. It's not that I doubt the developer's abilities, but just that it's a risk to consider for the longevity of the project.

Iced

Iced was actually my original gateway for getting into Rust in the first place. However, I have some serious doubts about its performance. It's possible that performance can be improved in future updates to Iced, but it's currently a gamble.

Pros

- Iced is by far the most mature native Rust GUI library.

- It gets financial backing from a few companies (albeit fairly small companies).

- It recently got adoption by System76 who are also interested in accelerating its development.

Cons

- On every update cycle, Iced reconstructs an entire abstract representation of the widget tree, diffs it with the previous widget tree, and then applies the necessary updates. While Iced touts that constructing this abstract tree and diffing it "should be cheap", I'm skeptical of how well it scales to a very large GUI.

- Iced doesn't use damage tracking for rendering. It's possible this could change in the future, but again it's a gamble.

- It's still missing a few key features such as proper multi-window support.

Custom in-house solution

For a while I was working on a concept called Firewheel. The main idea was that it's a low-level GUI library where the user manually updates the widget tree, manually lays out the widgets (with a simple but powerful "anchor" system), and manually assigns widgets to layers to most optimally take advantage of render regions.

However, developing an in-house toolkit most definitely falls into the "performance" corner of the triangle chart.

But as a counter-argument, because it's so low-level, maybe it won't actually take that much time to complete? A custom solution would also have the advantage of being in full control of the feature set.

Then again, it could just be too much work. I'd like to hear other people's opinions on this.

Non-Options

Here I'll list other existing native Rust GUI libraries and why I'm not considering them.

-

Druid

- It's no longer being updated and is in maintenance mode.

- Its performance isn't much better (or possibly even worse) than Iced.

- It doesn't use damage tracking for rendering.

-

slint

- It prioritizes using declarative markup files to construct the GUI. While I think you can use it in a non-declarative way, I'm not sure how well this works in practice.

- Its support for custom widgets is quite limited.

- Desktop platform support is currently unfinished, and I'm not sure it will even end up supporting all the features I need.

- Its GPU-based renderer currently doesn't use damage tracking, only its CPU-based renderer does.

-

imgui

- immediate-mode

-

makepad

- immediate-mode

-

tauri

- web-based

-

OrbTK

- No longer maintained

Options using Rust bindings

There is only one I think has any potential to fit my use case.

GTK

I've used gtk-rs in a previous attempt at Meadowlark's GUI. They are bindings to the GTK GUI library which is written in C (and is used by a lot of Linux applications). But again I have some concerns with it:

Pros

- There is already a DAW that uses GTK4 called Zrythm (albeit the developer uses C not Rust).

- Ardour also uses GTK (although it's a very old and heavily modified version of GTK2).

- It uses damage tracking for its rendering and is quite efficient even on complex GUIs.

- GTK is battle-tested and has a lot of developers behind it.

Cons

- THE BIGGEST deal breaker for me was that it doesn't have a way for widgets to listen to relative mouse movements as opposed to absolute mouse coordinates. Currently if you are dragging a knob/slider and the mouse hits the edge of the screen (or even outside a floating window), it will stop working. This might not be a problem for Zrythm since its only parameters are mixer tracks with large sliders, but for Meadowlark I want a horizontal FX rack like in Bitwig/Ableton. Horizontal FX racks have a lot of knobs/sliders near the bottom of the screen.

- It seems like adding this feature to GTK would be difficult. I might be able to do it myself given enough time, but even then will those changes be accepted upstream? And even then I'll have to wait for the Rust bindings to catch up.

- CSS styling is finicky.

- Support for Windows/Mac definitely takes a backseat to Linux support.

- I've run into an issue where text on Windows is straight up messed up even in the default demo. It seems to be getting a fix, but still that's several months after I posted the issue.

- I'm also just unsure about the direction that the Gnome team is taking with GTK as a whole (especially the whole controversy with libadwaita). This is a minor nitpick, but still.

Another potential solution I'll throw out there is maybe we just don't have knobs in Meadowlark, only sliders? It's not ideal, but considering that relative mouse movement support is the only real deal breaker I have with GTK, maybe it's an acceptable tradeoff?

Options using C++

Unfortunately using Rust bindings to these are either nonexistent or are practically unusable due to the incompatible philosophies between Rust and C++. So this means I would need to write Meadowlark's frontend in C++ if I go with one of these options.

FLTK

Pros

- Very efficient.

- Excellent support for custom OpenGL shaders.

- The (possibly abandoned?) Non DAW project uses it (or at least a modified version of it).

Cons

- I haven't yet looked into if it actually has all the features I need. Still, it seems quite promising.

JUCE

Pros

- It's already touted as a GUI library for audio applications.

- It also has a lot of other audio-related features such as connecting to system devices, meaning we wouldn't need to develop our own solutions such as rainout.

- It also has features like loading audio files and streaming them from disk, meaning we wouldn't need our own solutions such as creek and pcm-loader (although those two are already pretty much complete).

Cons

- Its performance can be quite poor even for a CPU-rendered library. Still, it uses damage tracking, and there are workarounds to greatly improve performance in areas.

- It's owned by PACE Anti-Piracy Inc. 🤢

QT

Pros

- No shortage of features.

Cons

- Its signal architecture can lead to buggy and hard-to-maintain spaghetti code (there are some ways to make it more manageable though).

- Its styling system is finicky. It could be tricky to support user-generated themes.

Development plan?

The final question I want an answer to is what is the best way to go about actually developing Meadowlark's frontend? By this I mean who actually does the work of developing it?

No matter what GUI library I choose, developing the frontend is going to take a lot of work due to how complex the logic is.

A part of me is starting to feel like maybe I've bitten off more than I can chew. If I were a company I would just hire a frontend developer, but Meadowlark is currently unfunded so I don't have that luxury (well there's a tiny bit of donations coming in, but definitely not enough to hire anyone).

Now this being an open source project, maybe I could leverage volunteers? However, I'm not sure how well volunteer-driven work will pan out considering just how complex the frontend is. I'm not sure any amount of drafting design documents (which also take quite a bit of work to create) would fix that issue. Ideally I would love if there was one or two people who could dedicated a large amount of time to the frontend. However, I haven't found anyone who is able or willing to do this amount of work for free, and I of course don't blame them for that.

And if you are wondering how I am currently financially supporting myself, I am fortunate enough to have supportive parents to fall back on. I'm currently living at their house on a farm.

I am using this opportunity to try and get Meadowlark off the ground before I start worrying about funding.

Another reason I brought up potentially using C++ is that developers (especially those with experience in the audio industry or the desktop GUI industry) are much harder to come by. If I go with a Rust library, not only will volunteers/employees need to learn Rust, but also the experimental GUI library itself (and Rust GUI libraries tend to have some pretty foreign concepts).

But on the flip-side, maybe the frontend is something I can handle by myself? Maybe I'm just doubting my own abilities too much? I'm not sure. In the end I just want to make sure that I'm allocating my time and resources wisely.

Still, if I do this solo, I think creating some design documents is probably a good idea just to help wrap my head around the complexity.

Final thoughts

After writing this, I'm now kind-of leaning towards the idea of using the Rust bindings to GTK and only having sliders in Meadowlark. It's probably possible to do what Tracktion Waveform does for some of its sliders, which is to show a large pop-up slider when dragging a small slider in order to save space while still allowing for a large degree of control.

But of course I would like to hear any thoughts and ideas you may have. I am most active in my Discord server if you are interested in discussion.

[ comments ]