Will the amateur airwaves fall silent? Since the dawn of radio, amateur operators—hams—have transmitted on tenaciously guarded slices of spectrum. Electronic engineering has benefited tremendously from their activity, from the level of the individual engineer to the entire field. But the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, with its ability to easily connect billions of people, captured the attention of many potential hams. Now, with time taking its toll on the ranks of operators, new technologies offer opportunities to revitalize amateur radio, even if in a form that previous generations might not recognize.

The number of U.S. amateur licenses has held at an anemic 1 percent annual growth for the past few years, with about 7,000 new licensees added every year for a total of 755,430 in 2018. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission doesn’t track demographic data of operators, but anecdotally, white men in their 60s and 70s make up much of the population. As these baby boomers age out, the fear is that there are too few young people to sustain the hobby.

“It’s the $60,000 question: How do we get the kids involved?” says Howard Michel, former CEO of the American Radio Relay League (ARRL). (Since speaking with IEEE Spectrum, Michel has left the ARRL. A permanent replacement has not yet been appointed.)

This question of how to attract younger operators also reveals deep divides in the ham community about the future of amateur radio. Like any large population, ham enthusiasts are no monolith; their opinions and outlooks on the decades to come vary widely. And emerging digital technologies are exacerbating these divides: Some hams see them as the future of amateur radio, while others grouse that they are eviscerating some of the best things about it.

No matter where they land on these battle lines, however, everyone understands one fact. The world is changing; the amount of spectrum is not. And it will be hard to argue that spectrum reserved for amateur use and experimentation should not be sold off to commercial users if hardly any amateurs are taking advantage of it.

Before we look to the future, let’s examine the current state of play. In the United States, the ARRL, as the national association for hams, is at the forefront, and with more than 160,000 members it is the largest group of radio amateurs in the world. The 106-year-old organization offers educational courses for hams; holds contests where operators compete on the basis of, say, making the most long-distance contacts in 48 hours; trains emergency communicators for disasters; lobbies to protect amateur radio’s spectrum allocation; and more.

Michel led the ARRL between October 2018 and January 2020, and he fits easily the profile of the “average” American ham: The 66-year-old from Dartmouth, Mass., credits his career in electrical and computer engineering to an early interest in amateur radio. He received his call sign, WB2ITX, 50 years ago and has loved the hobby ever since.

“When our president goes around to speak to groups, he’ll ask, ‘How many people here are under 20 [years old]?’ In a group of 100 people, he might get one raising their hand,” Michel says.

ARRL does sponsor some child-centric activities. The group runs twice-annual Kids Day events, fosters contacts with school clubs across the country, and publishes resources for teachers to lead radio-centric classroom activities. But Michel readily admits “we don’t have the resources to go out to middle schools”—which are key for piquing children’s interest.

Sustained interest is essential because potential hams must clear a particular barrier before they can take to the airwaves: a licensing exam. Licensing requirements vary—in the United States no license is required to listen to ham radio signals—but every country requires operators to demonstrate some technical knowledge and an understanding of the relevant regulations before they can get a registered call sign and begin transmitting.

For those younger people who are drawn to ham radio, up to those in their 30s and 40s, the primary motivating factor is different from that of their predecessors. With the Internet and social media services like WhatsApp and Facebook, they don’t need a transceiver to talk with someone halfway around the world (a big attraction in the days before email and cheap long-distance phone calls). Instead, many are interested in the capacity for public service, such as providing communications in the wake of a disaster, or event comms for activities like city marathons.

“There’s something about this post-9/11 group, having grown up with technology and having seen the impact of climate change,” Michel says. “They see how fragile cellphone infrastructure can be. What we need to do is convince them there’s more than getting licensed and putting a radio in your drawer and waiting for the end of the world.”

New Frontiers

The future lies in operators like Dhruv Rebba (KC9ZJX), who won Amateur Radio Newsline’s 2019 Young Ham of the Year award. He’s the 15-year-old son of immigrants from India and a sophomore at Normal Community High School in Illinois, where he also runs varsity cross-country and is active in the Future Business Leaders of America and robotics clubs. And he’s most interested in using amateur radio bands to communicate with astronauts in space.

Rebba earned his technician class license when he was 9, after having visited the annual Dayton Hamvention with his father. (In the United States, there are currently three levels of amateur radio license, issued after completing a written exam for each—technician, general, and extra. Higher levels give operators access to more radio spectrum.)

“My dad had kind of just brought me along, but then I saw all the booths and the stalls and the Morse code, and I thought it was really cool,” Rebba says. “It was something my friends weren’t doing.”

He joined the Central Illinois Radio Club of Bloomington, experimented with making radio contacts, participated in ARRL’s annual Field Days, and volunteered at the communications booths at local races.

But then Rebba found a way to combine ham radio with his passion for space: He learned about the Amateur Radio on the International Space Station (ARISS) program, managed by an international consortium of amateur radio organizations, which allows students to apply to speak directly with crew members onboard the ISS. (There is also an automated digital transponder on the ISS that allows hams to ping the station as it orbits.)

Rebba rallied his principal, science teacher, and classmates at Chiddix Junior High, and on 23 October 2017, they made contact with astronaut Joe Acaba (KE5DAR). For Rebba, who served as lead control operator, it was a crystallizing moment.

“The younger generation would be more interested in emergency communications and the space aspect, I think. We want to be making an impact,” Rebba says. “The hobby aspect is great, but a lot of my friends would argue it’s quite easy to talk to people overseas with texting and everything, so it’s kind of lost its magic.”

That statement might break the hearts of some of the more experienced hams recalling their tinkering time in their childhood basements. But some older operators welcome the change.

Take Bob Heil (K9EID), the famed sound engineer who created touring systems and audio equipment for acts including the Who, the Grateful Dead, and Peter Frampton. His company Heil Sound, in Fairview Heights, Ill., also manufactures amateur radio technology.

“I’d say wake up and smell the roses and see what ham radio is doing for emergencies!” Heil says cheerfully. “Dhruv and all of these kids are doing incredible things. They love that they can plug a kit the size of a cigar box into a computer and the screen becomes a ham radio…. It’s all getting mixed together and it’s wonderful.”

But there are other hams who think that the amateur radio community needs to be much more actively courting change if it is to survive. Sterling Mann (N0SSC), himself a millennial at age 27, wrote on his blog that “Millennials Are Killing Ham Radio.”

It’s a clickbait title, Mann admits: His blog post focuses on the challenge of balancing support for the dominant, graying ham population while pulling in younger people too. “The target demographic of every single amateur radio show, podcast, club, media outlet, society, magazine, livestream, or otherwise, is not young people,” he wrote. To capture the interest of young people, he urges that ham radio give up its century-long focus on person-to-person contacts in favor of activities where human to machine, or machine to machine, communication is the focus.

These differing interests are manifesting in something of an analog-to-digital technological divide. As Spectrum reported in July 2019, one of the key debates in ham radio is its main function in the future: Is it a social hobby? A utility to deliver data traffic? And who gets to decide?

Those questions have no definitive or immediate answers, but they cut to the core of the future of ham radio. Loring Kutchins, president of the Amateur Radio Safety Foundation, Inc. (ARSFi)—which funds and guides the “global radio email” system Winlink—says the divide between hobbyists and utilitarians seems to come down to age.

“Younger people who have come along tend to see amateur radio as a service, as it’s defined by FCC rules, which outline the purpose of amateur radio—especially as it relates to emergency operations,” Kutchins (W3QA) told Spectrum last year.

Kutchins, 68, expanded on the theme in a recent interview: “The people of my era will be gone—the people who got into it when it was magic to tune into Radio Moscow. But Grandpa’s ham radio set isn’t that big a deal compared to today’s technology. That doesn’t have to be sad. That’s normal.”

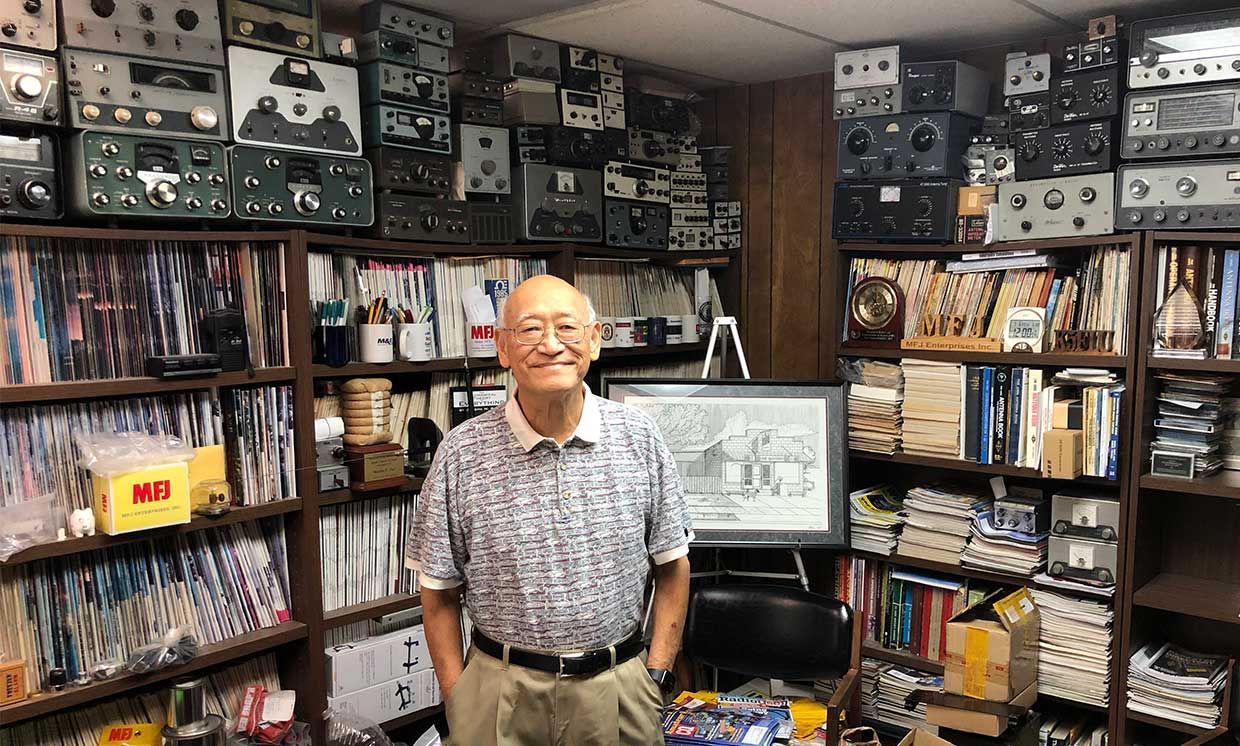

Gramps’ radios are certainly still around, however. “Ham radio is really a social hobby, or it has been a very social hobby—the rag-chewing has historically been the big part of it,” says Martin F. Jue (K5FLU), founder of radio accessories maker MFJ Enterprises, in Starkville, Miss. “Here in Mississippi, you get to 5 or 6 o’ clock and you have a big network going on and on—some of them are half-drunk chattin’ with you. It’s a social group, and they won’t even talk to you unless you’re in the group.”

But Jue, 76, notes the ham radio space has fragmented significantly beyond rag-chewing and DXing (making very long-distance contacts), and he credits the shift to digital. That’s where MFJ has moved with its antenna-heavy catalog of products.

“Ham radio is connected to the Internet now, where with a simple inexpensive handheld walkie-talkie and through the repeater systems connected to the Internet, you’re set to go,” he says. “You don’t need a HF [high-frequency] radio with a huge antenna to talk to people anywhere in the world.”

To that end, last year MFJ unveiled the RigPi Station Server: a control system made up of a Raspberry Pi paired with open-source software that allows operators to control radios remotely from their iPhones or Web browser.

“Some folks can’t put up an antenna, but that doesn’t matter anymore because they can use somebody else’s radio through these RigPis,” Jue says.

He’s careful to note the RigPi concept isn’t plug and play—“you still need to know something about networking, how to open up a port”—but he sees the space evolving along similar lines.

“It’s all going more and more toward digital modes,” Jue says. “In terms of equipment I think it’ll all be digital at some point, right at the antenna all the way until it becomes audio.”

The Signal From Overseas

Outside the United States, there are some notable bright spots, according to Dave Sumner (K1ZZ), secretary of the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU). This collective of national amateur radio associations around the globe represents hams’ interests to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a specialized United Nations agency that allocates and manages spectrum. In fact, in China, Indonesia, and Thailand, amateur radio is positively booming, Sumner says.

China’s advancing technology and growing middle class, with disposable income, has led to a “dramatic” increase in operators, Sumner says. Indonesia is subject to natural disasters as an island nation, spurring interest in emergency communication, and its president is a licensed operator. Trends in Thailand are less clear, Sumner says, but he believes here, too, that a desire to build community response teams is driving curiosity about ham radio.

“So,” Sumner says, “you have to be careful not to subscribe to the notion that it’s all collapsing everywhere.”

China is also changing the game in other ways, putting cheap radios on the market. A few years ago, an entry-level handheld UHF/VHF radio cost around US $100. Now, thanks to Chinese manufacturers like Baofeng, you can get one for under $25. HF radios are changing, too, with the rise of software-defined radio.

“It’s the low-cost radios that have changed ham radio and the future thereof, and will continue to do so,” says Jeff Crispino, CEO of Nooelec, a company in Wheatfield, N.Y., that makes test equipment and software-defined radios, where demodulating a signal is done in code, not hardwired electronics. “SDR was originally primarily for military operations because they were the only ones who could afford it, but over the past 10 years, this stuff has trickled down to become $20 if you want.” Activities like plane and boat tracking, and weather satellite communication, were “unheard of with analog” but are made much easier with SDR equipment, Crispino says.

Nooelec often hears from customers about how they’re leveraging the company’s products. For example, about 120 members from the group Space Australia to collect data from the Milky Way as a community project. They are using an SDR and a low-noise amplifier from Nooelec with a homemade horn antenna to detect the radio signal from interstellar clouds of hydrogen gas.

“We will develop products from that feedback loop—like for hydrogen line detection, we’ve developed accessories for that so you can tap into astronomical events with a $20 device and a $30 accessory,” Crispino says.

Looking ahead, the Nooelec team has been talking about how to “flatten the learning curve” and lower the bar to entry, so that the average user—not only the technically adept—can explore and develop their own novel projects within the world of ham radio.

“It is an increasingly fragmented space,” Crispino says. “But I don’t think that has negative connotations. When you can pull in totally unique perspectives, you get unique applications. We certainly haven’t thought of it all yet.”

The ham universe is affected by the world around it—by culture, by technology, by climate change, by the emergence of a new generation. And amateur radio enthusiasts are a varied and vibrant community of millions of operators, new and experienced and old and young, into robotics or chatting or contesting or emergency communications, excited or nervous or pessimistic or upbeat about what ham radio will look like decades from now.

As Michel, the former ARRL CEO, puts it: “Every ham has [their] own perspective. What we’ve learned over the hundred-plus years is that there will always be these battles—AM modulation versus single-sideband modulation, whatever it may be. The technology evolves. And the marketplace will follow where the interests lie.”

About the Author

Julianne Pepitone is a freelance technology, science, and business journalist and a frequent contributor to IEEE Spectrum. Her work has appeared in print, online, and on television outlets such as Popular Mechanics, CNN, and NBC News.