When the pandemic hit, many American parents found themselves muddling through homeschooling for the first time—but Elizabeth Beall is an old pro: She’s been teaching her 13-year-old daughter from home since kindergarten. Over the years, Beall, who lives in California, has learned that homeschooling works best when it doesn’t just happen at home, so she slowly built up a network of parents—mostly moms—who share ideas in Facebook groups and sometimes get the kids together in person for educational and social activities. Beall has formed tight bonds with many of the moms—and they’ve found that the Facebook groups are handy places to swap tips and information. So in late April, when Beall noticed that a few of the moms had posted a video of two physicians talking about the coronavirus, she gamely clicked.

The two doctors, emergency medicine specialists from Bakersfield, California, said that social distancing to stop the spread of the virus could dangerously weaken the immune system. A former epidemiologist, Beall noticed right away that something was off: The doctors seemed to be cherry-picking data about how many people had contracted the disease and recovered, and their math just didn’t make sense. She was shocked to hear them advise parents to intentionally expose children to the coronavirus to achieve herd immunity—it seemed reckless, maybe even deadly. So, she waded into the comments and calmly pointed out the flaws.

Beall was pretty sure she knew where the video came from: Many of the roughly 200 moms in her groups, she said, also belonged to Facebook groups that opposed vaccines, and occasionally, the moms cross-posted memes or information. Recently, the anti-vaccine groups had taken up the cause of opposing states’ shelter-in-place orders, claiming the lockdown violated their personal freedoms.

In the past, Beall, a strong believer in vaccines, would often respectfully challenge any inaccurate information the other members shared. In pre-pandemic days, her friends had thanked her for her perspective and moved on. This was how things went for homeschool moms: Even when they disagreed, they were still a tribe.

But this time, the comments took a different turn. Instead of the friendly back-and-forth, Beall’s remarks were met with vitriol. It was “this flood of beliefs around public health measures being an assault on freedom and liberty, and slavery and Holocaust analogies, and conspiracy theories, and 5G and Bill Gates,” she recalls. “It just went on and on with an endless flood of anger toward public health in general and me personally for not going along with this narrative in the video.”

The biggest shock came when an old friend of Beall’s weighed in, a woman who, like almost all of the other moms in her circle, was “appalled when Donald Trump was elected president,” Beall remembers, saying “she cried tears over it.” Beall didn’t expect her to be so defensive of the video, and when she tried to explain that it was “being used by people on the very far right to promote a narrative that’s going to kill people,” she says the friend laid it all out in pretty harsh terms: “I would rather align myself,” she told Beall, “with those people who care about freedom, instead of someone like you, who wants to have us controlled and dominated by our government.”

Beall is still reeling from the encounter—and she can’t shake the feeling that something frightening has happened to her old friends. She’s almost certainly not alone; what she has experienced is actually representative of a broader trend.

Back when I started covering the anti-vaccination movement more than a decade ago, the loudest voices came from politically liberal, mostly white, and affluent enclaves—think famously hippie places like Marin County, California, or Boulder, Colorado—where parents worried about the side effects of what they perceive as toxins in vaccines. Anti-vaxxers in these places tended to pride themselves on the purity of their lifestyles—they bought organic groceries, railed against genetically modified food, and were suspicious of the electromagnetic waves emitted by cellphones. In a 2012 Parade magazine article, Seth Mnookin, author of The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear, described anti-vax clusters as places “where parents are often focused on being environmentally conscious and paying close attention to every aspect of their children’s development.”

For baby advice, many turned to attachment parenting guru Dr. Bob Sears, who encourages parents to skip or delay their babies’ vaccines to limit their exposure to toxins. When it came time for school, many chose Waldorf—the network of private schools that promotes the progressive and somewhat eccentric educational ideas of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner; these schools have had some of the lowest vaccination rates in the country (and at the same time have had outbreaks of whooping cough and chickenpox). “Breastfeeding, eating organic foods, insular communities—it was this archetype of a person,” says Rupali Limaye, a Johns Hopkins epidemiologist who has studied the movement against mandatory vaccines.

But over the last few years, Limaye has observed a subtle rightward shift: Online anti-vax communities, most of which are on Facebook, have taken on a very different tone. Instead of fretting over unwholesome additives in vaccines, members now rant about government overreach. They describe schools’ immunization rules as an assault on their freedom, and they swap theories about how Bill Gates is working with the government to control citizens with microchips, says Limaye. They’re “railing against the government and pharma companies controlling the population.”

Since the start of the pandemic, suspicion of the government has converged with a broad refusal to accept scientific evidence—one that has been enabled by President Trump—and it’s given the groups new points of reference: They’ve railed against shelter-in-place orders and masks. And in these radicalized spaces, misinformation thrives. Members share articles about how to cure the virus with vitamin C, and they pass around conspiracy videos like “Plandemic,” which argues that the virus is a moneymaking scheme perpetrated by an exclusive group of elites. Some individuals speculate that there is no virus at all.

Limaye worries that the cross-pollination between the anti-vax community and far-right groups could eventually cause an epidemic of vaccine skepticism. And if that happens, we’ll be in real trouble. Vaccines rank with indoor plumbing as one of the most important public health breakthroughs of modern history. They prevent millions of deaths worldwide every year. Yet experts warn that if global vaccination rates drop, we could see a resurgence of deadly diseases such as measles and polio. The anti-vax movement is “spilling over to the hesitant folks,” she says. “These folks might have been on the fence but leaning toward vaccination, and now that they hear about the overreach, they’re going to decide not to vaccinate.”

Most of us think of political culture in America as a spectrum—on one side is the far left, and way on the other is the far right. But occasionally, the spectrum is more of a circle, with the two extremes joining up in a strange middle point around back. Jennifer Reich, a University of Colorado Denver sociologist who studies the spread of misinformation about health, noticed this dynamic in vaccine hesitancy when she was first starting out in the field, back in 2007. “This was one of those places where right meets left, and that’s been true for a long time,” she said. In a 2017 study published in the journal Nature Human Behavior, Saad Omer, a Yale University epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist, studied this phenomenon, asking parents of about their values, political affiliation, and beliefs about vaccines. His team found that people who were skeptical of vaccines tended to list “purity” and “liberty” as important values. “Purity overlaps substantially with the ‘crunchy granola’ crowd,” Omer explained. But “liberty” is where things get interesting: “The left interpretation of liberty is human rights, and the right is libertarianism.”

Yet some experts believe that voices from the far right are beginning to drown out those of the crunchy granola crowd. Reich says that she started noticing the shift during the Obama presidency, right after the Affordable Care Act passed. Reich was working on a study about small business owners’ attitudes toward paying for employee health insurance. “When I suggested that Obamacare might help, they started talking about ‘womb to tomb’ government tracking,” she said. “I was definitely not expecting that.” Soon after, she started noticing comments about government overreach in anti-vax groups.

She also observed a rising tide of anti-science sentiment. Members of the groups she followed seemed to believe that they could become self-made experts by doing their own research, medical degrees and study design be damned. In her 2016 book Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines, Reich describes an encounter with one mother who introduced herself as a “vaccine researcher.” The woman wasn’t a scientist—she had simply read up on vaccines, the way one might research a product before buying it. “In calling herself a ‘vaccine researcher,’ a term usually referring to immunologists or microbiologists who spend decades in laboratories after years of postgraduate training, she challenges the very meaning of expertise and considers her qualification as a vigilant parent to be equivalent,” Reich wrote.

Meanwhile, Devin Burghart, executive director of the anti-white-nationalism think tank the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights, noticed the trend around the time Trump was elected president and the newly emboldened extremist groups found their way into the mainstream. “If there was really one thing to point to that was a transformative moment, it was Trump’s flirtation with anti-vax messaging that signaled to the MAGA base that this was something to be concerned about,” he said. Since taking office, Trump has supported the federal immunization program, but that’s a departure from a much longer history. As he was gearing up to run, he regularly repeated the myth that vaccines cause autism, and he once said a vaccine “looks like it’s meant for a horse, not for a child.”

The Trump administration has actively encouraged this kind of science denial: Doctors and scientists are intellectuals to be regarded with suspicion. By May 2019, Trump himself had publicly attacked science 100 times by Scientific American’s count. And the coronavirus has thrown a spark into that powder keg, as Americans watch scientists learn about the disease in real time, sometimes making big mistakes publicly. “Now it’s clear that science is messy,” Reich said. “If you’re being told you can’t go to a grocery store without a mask, and you’re reading conflicting reports, it becomes easy to question the validity of science.”

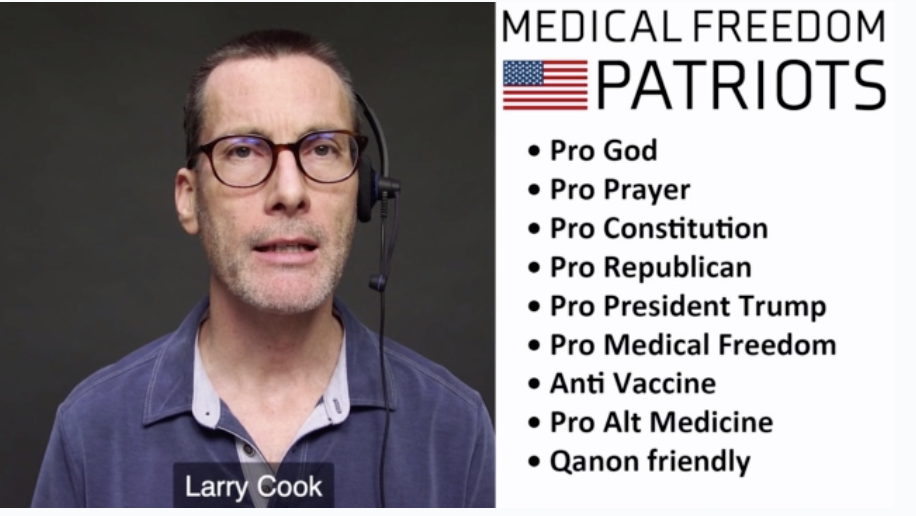

Burghart has documented the rightward shifts in many of the Facebook groups he monitors. He points to the influential Stop Mandatory Vaccination group, which was founded five years ago by California naturopath Larry Cook as a kind of clearinghouse for the alternative medicine community to share theories about how the toxins in vaccines could supposedly harm children. In one recent post, a member shared a link to a documentary called Sacrificial Virgins about the dangers of the HPV vaccine; in another, Cook proclaims, “Children’s Lives Matter: Defund the Vaccine Industry Killing Machine.” Earlier this year, Cook launched a spinoff group called Medical Freedom Patriots. The goal—to convince the world that vaccines are dangerous—was the same, but the new group was different in that its strategy was explicitly political: Cook explains in a video on the new website how his thinking evolved on spreading his anti-vaccine message. “The Democrats are actually the ones pushing the vaccine mandate agenda,” he says. “I am of the opinion that now, especially with COVID-19, the Republican elected officials are going to get hit really, really, really hard to capitulate to vaccine mandates.” He goes on to explain that the goal of his new group is to reach his “target demographic,” the far right:

Cook’s group isn’t the only one targeting the political right: Members of Facebook anti-vax groups now regularly post pro-Trump messages and videos. The group Michigan for Vaccine Choice shared a Trump campaign video that reassures voters that the president wouldn’t force Americans to get a coronavirus vaccine once it’s developed. The group Indiana Coalition for Vaccine Choice invited users to a Memorial Day “Freedom Raly” cosponsored by the Conservative Alliance and the local chapter of the tea party. And many groups are littered with references to QAnon, the conspiracy theory group whose adherents believe, among other things, that a secretive elite group wants to unseat Trump.

Anti-vaccine groups’ efforts to court Republicans have started to pay off. In the last few years, conservative lawmakers in several states have introduced legislation that seeks to weaken rules around vaccination. In 2017, a group of Republican Texas state reps who called themselves the Freedom Caucus sought to block the state’s effort to track the number of parents who sought exemptions for schools’ vaccine requirements. The Freedom Caucus passed an amendment that requires the state to obtain parental consent from biological parents before vaccinating children in foster care. A Pennsylvania state senator, Daryl Metcalfe, sponsored a bill in 2019 that would prohibit doctors from refusing to care for unvaccinated patients. In January, Colorado state Sen. Dave Williams introduced legislation that would require health care workers to give parents a list of ingredients and rare side effects before administering vaccines; it would also forbid them from even recommending a vaccine to a teenager without parental consent. It didn’t pass, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. In the days leading up to the vote, the admins of the Facebook group People for Informed Consent exhorted members to “spend the next few days working the halls and working the phones like it is your only job. You must secure every Republican Senator and flip three Democrats.”

In 2018, researchers from Drexel University in Pennsylvania reviewed 175 proposed pieces of legislation about states’ vaccine exemption laws. They found that bills that sought to make it easier to opt out of vaccines were more likely to come from Republican lawmakers. Of the 13 bills that ultimately passed, 12 weakened existing laws around vaccine requirements.

The experts I talked to fell short of saying that right-wingers have entirely co-opted the movement—the crunchy old guard is still there, they assured me. Yale’s Omer pointed to left-wing politicians and celebrities—including lawyer Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and late-night host Bill Maher—who have continued to vociferously oppose vaccines. “I don’t think that the left side of the movement is going anywhere,” he says. Still, he sees a need to track the political dynamics—and government funding for research on the ideology behind vaccine refusal is scarce.

Brendan Nyhan, a Dartmouth College political science professor who studies the politicization of health information, pointed out that the majority of Americans still vaccinate their children. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 92 percent of 19-to 35-month-olds are up to date on their measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines. A 2017 Pew poll found that 82 percent of Americans believe that parents should be required to vaccinate healthy children. The survey didn’t find meaningful partisan differences in opinion, and some experts warned me to be careful about characterizing vaccines as a partisan issue—if mainstream Republicans begin to see vaccines as part of the Democrats’ agenda, they said, we’ll be in real trouble—especially going into a presidential election that could coincide with the introduction of a vaccine for COVID-19. “The prospect of a change” toward partisanship on vaccines, said Nyhan, “is worrisome.”

A few days after I spoke to Nyhan, as I was finishing up writing this piece, the Washington Post and ABC released the results of a poll. It found that 27 percent of Americans say they wouldn’t get a coronavirus vaccine. But when those numbers were broken down to include political affiliation, 80 percent of Democrats said they would “definitely or probably” get vaccinated, compared to just 60 percent of Republicans.

For Beall, the burgeoning divide has become personal: The experience in her homeschool Facebook groups was a turning point. After having enjoyed time spent with other members and their kids, she decided to limit her family’s real-life interaction with parents whose belief in conspiracies and suspicion of science she considers dangerous. “I don’t want my daughter to go back there, even though she’s made friends and had a great time,” she says. “I no longer trust that the adults in that community have any ability to model critical thinking skills for her. I just feel like that is a place so out of touch with reality.”