The later Thirties bring a few new twists into our cartoon curriculum. As we left off last week, the changing tastes of the music world had begun to react, big time, to the sweeping trends of big band swing, spearheaded by Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, and innumerable others – to the point where, at least for the animated world, “Swing” was added to the class list for any self-respecting toon. Following Betty Boop’s lead, other productions would carry the ball in this direction – including another chance for Betty herself to get into the act. Another new idea was a twist on the run of gangster and hoodlum pictures which had become a major genre for Warner Brothers, which in 1938 featured an entry entitled “Crime School”, starring Humphrey Bogart and several members of the group of youths commonly referred to as the “Dead End Kids”, showing life on the darker side of the educational experience, within the walls of a reform school for juvenile delinquents. Animation took its own twist on this idea, wondering what “education” might be like to train the youths to be delinquents in the first place, and contributes two such instances as chapters for our textbooks. Finally, animation provides during this period its first glimpses of the concept that its characters do not all have to receive their tutelage within the confines of the little red school house, and that higher education can be provided through the medium of the mail-order correspondence course. Correspondence learning was not a new idea per se, having existed through some universities as early as the 1850’s. However, it was organizing and becoming more popularly accepted, as evidenced by the first meeting of the International Conference for Correspondence Education in 1938. Thus, it was yet another “modern” trend for animators to capitalize upon.

Katnip Kollege (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 6/11/38 – Cal Dalton, Cal Howard, dir.). has been visited before in these columns. It holds a unique place in Warner carttoon history, being the only short in the series styled to closely resemble the musical shorts which the Vitaphone division of Warners had been turning out in live action for years. It is also unique in being the only Merrie Melodie to feature soundtrack portions which are directly edited from musical outtakes from the Warner feature, “Over the Goal”, featuring the uncredited vocals of Johnnie “Scat” Davis and Mabel Todd, with additional assist by the Pied Pipers.

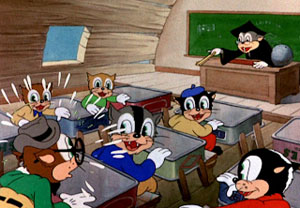

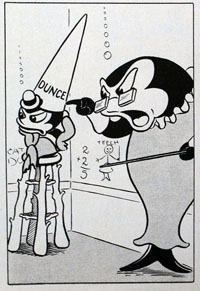

The scene opens at the doors of an all-cat university. The set design is rather unbelievable, as the university is depicted as built inside an old barrel, which from the outside looks only big enough to house one classron at best, but when seen from the interior has an entire hallway of classroom doors, including one for the campus’s most popular class, Swingology, where the rhythms from within nearly vibrate the door off its hinges. Inside, the class members clap time and beat out a rhythm, as the professor appears at the front of the class by means of a rising stage elevator built into the floor, performing a pecking dance step. He struts his stuff before the class’s syncopated rendition of “Good Morning to You”, with even an outline drawing of him on the blackboard dancing in step with him. Teacher begins to ask various students in rhyme to recite their homework lessons. They respond with verses of a musical history lessen, lifted from the lyrics of the song, :Let That Be a Lesson To You” from the feature, “Hollywood Hotel”. A star performance is entered by a miss Kitty Bright, the prettiest kitten in class, wearing a cute hat and monogrammed sweater. Everyone is in step except one tomcat in a back row, wearing nerd glasses, and trying desperately to clap at the same time as the rest of the class. “Now Johnnie, let’s hear your sonnets. Make them sound like Kostelanatz.” (An odd reference to Andre Kostelanatz, leader of a large orchestra which seemed to straddle the fence with light classical music only slightly flavored with modern rhythm influence.) Johnnie is a hopeless failure, as the best he can mutter is “Vo deo oh do, Charleston, a Razz a ma Tazz, and Boop Boop a Doop.” “Boy, is that corny”, says the upset professor, who calls Johnnie to the front of the class, and inti the corner, where Johnnie sits on a stool, and presses a wall button that elevates his seat upwards until his head makes contact with a suspended dunce cap also hanging in the corner. As the class is dismissed, various students taunt Johnnis with comments like “You swing like a rusty gate”. Kitty is the last to leave, and tosses Johnnie a pin from her sweater. “Here’s your old frat pin. You can look me up when you learn to swing.”

The scene opens at the doors of an all-cat university. The set design is rather unbelievable, as the university is depicted as built inside an old barrel, which from the outside looks only big enough to house one classron at best, but when seen from the interior has an entire hallway of classroom doors, including one for the campus’s most popular class, Swingology, where the rhythms from within nearly vibrate the door off its hinges. Inside, the class members clap time and beat out a rhythm, as the professor appears at the front of the class by means of a rising stage elevator built into the floor, performing a pecking dance step. He struts his stuff before the class’s syncopated rendition of “Good Morning to You”, with even an outline drawing of him on the blackboard dancing in step with him. Teacher begins to ask various students in rhyme to recite their homework lessons. They respond with verses of a musical history lessen, lifted from the lyrics of the song, :Let That Be a Lesson To You” from the feature, “Hollywood Hotel”. A star performance is entered by a miss Kitty Bright, the prettiest kitten in class, wearing a cute hat and monogrammed sweater. Everyone is in step except one tomcat in a back row, wearing nerd glasses, and trying desperately to clap at the same time as the rest of the class. “Now Johnnie, let’s hear your sonnets. Make them sound like Kostelanatz.” (An odd reference to Andre Kostelanatz, leader of a large orchestra which seemed to straddle the fence with light classical music only slightly flavored with modern rhythm influence.) Johnnie is a hopeless failure, as the best he can mutter is “Vo deo oh do, Charleston, a Razz a ma Tazz, and Boop Boop a Doop.” “Boy, is that corny”, says the upset professor, who calls Johnnie to the front of the class, and inti the corner, where Johnnie sits on a stool, and presses a wall button that elevates his seat upwards until his head makes contact with a suspended dunce cap also hanging in the corner. As the class is dismissed, various students taunt Johnnis with comments like “You swing like a rusty gate”. Kitty is the last to leave, and tosses Johnnie a pin from her sweater. “Here’s your old frat pin. You can look me up when you learn to swing.”

That night, as the moon rises, a jam session begins on the campus grounds, where the student body lounges to hear the tunes of a college combo. A glee club chimes in with lyrics about “the only use we’ve found so far for corn is when you pop it.” The band’s music wafts back to the classroom where Johnnie still sits under the dunce cap. Johnnie notices that the pendulum of the clock on the wall is in sync with the music he is hearing, and begins to sway his head in pecking fashion to match the movements of the pendulum. Dawn finally breaks that this is the sense of timing he was lacking. “I got it! The rhythm bug bit me. La de ah!”, says Johnnie, and with a final double check that he can still match the clock movement, he zooms out the door to where the band is playing. To the surprise of all, especially Kitty, he launches into his own musical number, “As Easy As Rolling Off a Log” (the outtake from “Over the Goal”), which provides the musical setting for the remainder of the cartoon, framed as a production number duet between Johnny and Kitty, dancing atop a log Kitty was sitting on. Johnny climaxes with a hot trumpet solo, extending his musical talents beyond mere vocal, and the two end the number by literally falling off the log in question, with Kutty rising from behind it, covering Johnnie’s face with kisses for the iris out.

That night, as the moon rises, a jam session begins on the campus grounds, where the student body lounges to hear the tunes of a college combo. A glee club chimes in with lyrics about “the only use we’ve found so far for corn is when you pop it.” The band’s music wafts back to the classroom where Johnnie still sits under the dunce cap. Johnnie notices that the pendulum of the clock on the wall is in sync with the music he is hearing, and begins to sway his head in pecking fashion to match the movements of the pendulum. Dawn finally breaks that this is the sense of timing he was lacking. “I got it! The rhythm bug bit me. La de ah!”, says Johnnie, and with a final double check that he can still match the clock movement, he zooms out the door to where the band is playing. To the surprise of all, especially Kitty, he launches into his own musical number, “As Easy As Rolling Off a Log” (the outtake from “Over the Goal”), which provides the musical setting for the remainder of the cartoon, framed as a production number duet between Johnny and Kitty, dancing atop a log Kitty was sitting on. Johnny climaxes with a hot trumpet solo, extending his musical talents beyond mere vocal, and the two end the number by literally falling off the log in question, with Kutty rising from behind it, covering Johnnie’s face with kisses for the iris out.

Hollywood Graduation (Charles Mintz/Columbia, 8/26/38 – Art Davis, dir.), is a largely unknown commodity, having seemingly disappeared from the vault holdings at Columbia/Sony. To date, no viewable prints have turned up on the internet, though a few extremely brief fragmentary shots once appeared on a reel of miscellaneous nitrate fragments posted on the Thunderbean Thursday columns of this website. However, a reasonable, albeit short, plot description has somehow materialized on the pages of IMDB, perhaps culled from trade reviews of the day (unless someone with a complete print is holding out from the rest of us). Said review is as follows:

Hollywood Graduation (Charles Mintz/Columbia, 8/26/38 – Art Davis, dir.), is a largely unknown commodity, having seemingly disappeared from the vault holdings at Columbia/Sony. To date, no viewable prints have turned up on the internet, though a few extremely brief fragmentary shots once appeared on a reel of miscellaneous nitrate fragments posted on the Thunderbean Thursday columns of this website. However, a reasonable, albeit short, plot description has somehow materialized on the pages of IMDB, perhaps culled from trade reviews of the day (unless someone with a complete print is holding out from the rest of us). Said review is as follows:

“A dramatic school for children is holding graduation ceremonies in a huge auditorium. We see the kids are caricatures of Hollywood film stars, including Wallace Beery, Herman Bing, Joe E. Brown, Claudette Colbert, Stepin Fetchit, Kay Francis, Clark Gable, Hugh Herbert, Charles Laughton, Peter Lorre, Marx Brothers, Three Stooges, and many others. The headmaster, trying to hand out diplomas, is harassed by kids on the stage, leaving him fumbling with his loose toupee, spectacles and dentures. Leopold Stakowski leads the orchestra playing for child Martha Raye’s singing.”

Charles Mintz’s studio was certainly not the first to feature celebrity caricatures in its cartoons (which practice dates back into the silent days). However, he may have been a trendsetter in providing glimpses of galleries of celebrity impersonations within the same cartoon, beginning with Krazy Kat’s 1932-33 season opener, “Seeing Stars” – predating by over half a year Mickey Mouse’s first meeting with Hollywood’s finest in “Mickey’s Gala Premier”. While Warner Brothers would subsequently also become a Mecca for the caricature cartoon, Mintz and his successors at Screen Gems would retain, and frequently fall back upon, this type of picture as a sub-genre, trotting out the same personalities (along with many new ones) again and again for recurring visits, crossing into virtually every series of cartoons the studio produced, in both black and white and color. Hollywood was not the only target for the Mintz animators’ pens, as they became equally adept at caricatures of significant world leaders, and of virtually anyone else from other walks of life who rose to public notoriety (including Al Capone), in other episodes such as “Scrappy’s Party” and “The World’s Affair”. Many times, the setups were clever and entertaining – but on other occasions, the reappearances got a bit tiring and monotonous, almost as if the cameos were present again just to allow for a quick-and-dirty cheater film. This became exceptionally evident during the color productions, where several shots were archived for reuse in two to three other cartoons which followed. So there’s no telling if any reused material appears in “Graduation”, or how much of it was creatively original. Art Davis, being one of the better directors to spring from the studio, may have perhaps provided the film with some new life and reason for being. It is sad that we don’t have ready means of making these determinations from experiencing the director’s intended concept.

Sally Swing (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 10/14/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Gordon Sheehan, anim.) – Another lively musical outing for the series, although Betty herself definitely plays second fiddle to the uncredited guest artist – none other than Rose Marie (later of fame on Dick Van Dyke and the Hollywood Squares), no longer a “Baby”, but still able to scat a mean swing number. In the hall of science of a prestigious university, Betty Boop, a faculty member, maintains a private examination room. However, this day she is not conducting tests or grading exams. She is deep in thought with a couple of student body leaders over rounding up the talent to perform at a big dance to be held on campus. While the two students are in agreement with her that the act they need is a musical aggregation, they are both structly squares, and their efforts to jazz up “Good Night, Ladies” just fail to put Betty into the groove. Betty pulls a lever behind her desk, activating a carpet to act as an early version of George Jetson’s traveling sidewalks, ushering the singer out the door, where he stumbles on a bar of soap left on the floor by a cleaning lady in the corridor, and makes a surprise hasty exit from the building. Betty looks over other student talent prospects in her outer waiting room. They are all out of step with the times or the theme of the evening, none of them showing any potential for swing (including a wanna-be Joe Penner type who wants to know if Betty wants to buy a duck, a ventriloquist with a dummy who sounds like Charlie McCarthy, and a pair of vaudevillain types who perform a Russian dance climaxed by the phrase, “Good Evening, Friends”). The situation looks hopeless, and Betty dismisses all the wanna-bes, and paces the floor in her inner office to try to get an idea where to find a swing band leader.

Sally Swing (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 10/14/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Gordon Sheehan, anim.) – Another lively musical outing for the series, although Betty herself definitely plays second fiddle to the uncredited guest artist – none other than Rose Marie (later of fame on Dick Van Dyke and the Hollywood Squares), no longer a “Baby”, but still able to scat a mean swing number. In the hall of science of a prestigious university, Betty Boop, a faculty member, maintains a private examination room. However, this day she is not conducting tests or grading exams. She is deep in thought with a couple of student body leaders over rounding up the talent to perform at a big dance to be held on campus. While the two students are in agreement with her that the act they need is a musical aggregation, they are both structly squares, and their efforts to jazz up “Good Night, Ladies” just fail to put Betty into the groove. Betty pulls a lever behind her desk, activating a carpet to act as an early version of George Jetson’s traveling sidewalks, ushering the singer out the door, where he stumbles on a bar of soap left on the floor by a cleaning lady in the corridor, and makes a surprise hasty exit from the building. Betty looks over other student talent prospects in her outer waiting room. They are all out of step with the times or the theme of the evening, none of them showing any potential for swing (including a wanna-be Joe Penner type who wants to know if Betty wants to buy a duck, a ventriloquist with a dummy who sounds like Charlie McCarthy, and a pair of vaudevillain types who perform a Russian dance climaxed by the phrase, “Good Evening, Friends”). The situation looks hopeless, and Betty dismisses all the wanna-bes, and paces the floor in her inner office to try to get an idea where to find a swing band leader.

Suddenly, the answer comes to her as if by a miracle. In the inner corridor of the building, Betty sees through the glass door of her office the silhouette of the cleaning woman, gently scatting a tune to herself, and moving with the steps of a jutterbug while she cleans the glass panel of Betty’s door. Betty runs outside, grabs the girl by the hand, and ushers her inside as just the person she needs. “What have yor been doing scrubbing? You should be cleaning up!” says Betty in excited mile-a-minute dialogue. Telephining the student body president, Boop says she has someone she knows the students will love. The scene neatly dissolves to the night of the big dance, with Betty, as mistress of ceremonies, continuing her praise and introduction of her new find over the stage microphone to the entire student body. The cleaning woman has been spruced up in a jazzy new outfit and long flowing hair, and has been dubbed by Betty, “Sally Swing”. Before a bandstand containing a newly organized student orchestra, the microphone is turned over to Sally, and she cuts loose with a snappy theme song, low growling scat vocals, and energetic dancing. The band is inspired by her energy and tempo, and the clarinetist begins to play so “red hot” that his instrument catches fire, and has to be doused in a bucket of water. The audience also loves her, and dances wildly to her beat, while Betty claps out time from the wings, and encourages Sally to “knock ‘em in the aisles.” The Dean, watching from a private table in the back of the hall, is the only sour face in the room. He believes the abandon has gone too far, and calls for everyone to stop. “I am the principal, and it’s against my principles”, he shouts to no avail, being drowned out by the music. He makes his way up on stage, but being so close to Sally’s gyrations and pecking, he involuntarily finds himself copying her movements – until he can’t help himself, and is taken with the rhythm too. Betty joins them both on stage, and the three perform some precision unison dance moves together, until someone tosses up to the stage a cap and gown, which land on Sally, making her an honorary graduate with a major in music, for the iris out.

Suddenly, the answer comes to her as if by a miracle. In the inner corridor of the building, Betty sees through the glass door of her office the silhouette of the cleaning woman, gently scatting a tune to herself, and moving with the steps of a jutterbug while she cleans the glass panel of Betty’s door. Betty runs outside, grabs the girl by the hand, and ushers her inside as just the person she needs. “What have yor been doing scrubbing? You should be cleaning up!” says Betty in excited mile-a-minute dialogue. Telephining the student body president, Boop says she has someone she knows the students will love. The scene neatly dissolves to the night of the big dance, with Betty, as mistress of ceremonies, continuing her praise and introduction of her new find over the stage microphone to the entire student body. The cleaning woman has been spruced up in a jazzy new outfit and long flowing hair, and has been dubbed by Betty, “Sally Swing”. Before a bandstand containing a newly organized student orchestra, the microphone is turned over to Sally, and she cuts loose with a snappy theme song, low growling scat vocals, and energetic dancing. The band is inspired by her energy and tempo, and the clarinetist begins to play so “red hot” that his instrument catches fire, and has to be doused in a bucket of water. The audience also loves her, and dances wildly to her beat, while Betty claps out time from the wings, and encourages Sally to “knock ‘em in the aisles.” The Dean, watching from a private table in the back of the hall, is the only sour face in the room. He believes the abandon has gone too far, and calls for everyone to stop. “I am the principal, and it’s against my principles”, he shouts to no avail, being drowned out by the music. He makes his way up on stage, but being so close to Sally’s gyrations and pecking, he involuntarily finds himself copying her movements – until he can’t help himself, and is taken with the rhythm too. Betty joins them both on stage, and the three perform some precision unison dance moves together, until someone tosses up to the stage a cap and gown, which land on Sally, making her an honorary graduate with a major in music, for the iris out.

The Disobedient Mouse (Lantz/Universal, Baby Face Mouse, 11/1/38. Les Kline, dir.) – Baby Face Mouse is trying to get out of the house for a day of play, but cornered by his mother with instructions to play in his own neighborhood, and not to cross the railroad tracks. In literal fashion, with Mom’s words appearing in printed letters sailing through the air, her words go through Baby Face, in one ear and out the other. Baby Face grumbles as he walks along the road that Mom has too many rules, and that she should know he can take care of himself, pushing his little hat into a rakish angle partially covering his eyes, in the manner of a little tough guy. Not seeing too well where he is going, Baby Face suddenly discovers that his feet have encountered the railroad tracks dividing the good and bad sections of town, and he is partway across the railroad ties. He darts back to the side he came from, nervously following his mother’s advice. But his wandering eyes clearly indicate the temptation to see what’s just over the line, and how the other half lives. He toys with the boundary, taking a few tenuous steps, one foot in front of the other, along the top of the rail closest to him. Then, an idea percolates – if his hat were to end up on the other side of the tracks, he’d have to go and get it. When he is sure no one is looking, he tosses the hat across the tracks, then, making doubly sure to look out for anyone observing, crosses over to it. Just so his visit isn’t a mere brief one, he pretends to reach down for the hat, but in stepping forward, deliberately boots the hat several feet down the street. The ploy working, he repeats the process again and again, coyly remarking to the audience how clumsy he is today. Ahead of him, however, stands open the doorway to a shady and unknown establishment, out of which peers a large rat. “Aha”, says the rat at observing the mouse approaching. When the hat is kicked within range of the doorway, the rat grabs the chapeau, and disappears inside. Baby Face is surprised and puzzled by the mystery hand and the hat’s disappearance, and cautiously ventures into the darkened doorway. A slam of the door is heard by him from within the darkness, and the lights go up to reveal the rat. “This your hat?”, asks the rat. Baby face gulps in fear, but feigns a grin as he acknowledges ownership, takes his cap back, then politely states he must be going. “I don’t think you’ll go”, says the rat, pushing the mouse backwards and through a trap door, down a flight of stairs into the cellar. “Welcome to Professor Rat-Face’s Crime School”, says the rat, following downstairs and picking up Baby Face by the tail to deposit him Into a seat. Baby Face finds himself alone in a class of one, as the rat places a professor’s mortarboard on his head, and calls class to order.

The Disobedient Mouse (Lantz/Universal, Baby Face Mouse, 11/1/38. Les Kline, dir.) – Baby Face Mouse is trying to get out of the house for a day of play, but cornered by his mother with instructions to play in his own neighborhood, and not to cross the railroad tracks. In literal fashion, with Mom’s words appearing in printed letters sailing through the air, her words go through Baby Face, in one ear and out the other. Baby Face grumbles as he walks along the road that Mom has too many rules, and that she should know he can take care of himself, pushing his little hat into a rakish angle partially covering his eyes, in the manner of a little tough guy. Not seeing too well where he is going, Baby Face suddenly discovers that his feet have encountered the railroad tracks dividing the good and bad sections of town, and he is partway across the railroad ties. He darts back to the side he came from, nervously following his mother’s advice. But his wandering eyes clearly indicate the temptation to see what’s just over the line, and how the other half lives. He toys with the boundary, taking a few tenuous steps, one foot in front of the other, along the top of the rail closest to him. Then, an idea percolates – if his hat were to end up on the other side of the tracks, he’d have to go and get it. When he is sure no one is looking, he tosses the hat across the tracks, then, making doubly sure to look out for anyone observing, crosses over to it. Just so his visit isn’t a mere brief one, he pretends to reach down for the hat, but in stepping forward, deliberately boots the hat several feet down the street. The ploy working, he repeats the process again and again, coyly remarking to the audience how clumsy he is today. Ahead of him, however, stands open the doorway to a shady and unknown establishment, out of which peers a large rat. “Aha”, says the rat at observing the mouse approaching. When the hat is kicked within range of the doorway, the rat grabs the chapeau, and disappears inside. Baby Face is surprised and puzzled by the mystery hand and the hat’s disappearance, and cautiously ventures into the darkened doorway. A slam of the door is heard by him from within the darkness, and the lights go up to reveal the rat. “This your hat?”, asks the rat. Baby face gulps in fear, but feigns a grin as he acknowledges ownership, takes his cap back, then politely states he must be going. “I don’t think you’ll go”, says the rat, pushing the mouse backwards and through a trap door, down a flight of stairs into the cellar. “Welcome to Professor Rat-Face’s Crime School”, says the rat, following downstairs and picking up Baby Face by the tail to deposit him Into a seat. Baby Face finds himself alone in a class of one, as the rat places a professor’s mortarboard on his head, and calls class to order.

The rat directs Baby Face to follow him over to a door frame without a wall, and a bottle of milk. First lesson is to swipe the milk without the owner catching you. Baby Face gently protests at the idea, insisting that crime doesn’t pay. “Quiet”, shouts the rat, slapping the mouse across the face with the back of his glove, “Don’t talk back to the teacher.” The rat cautions Baby Face that he must perform the task quickly, as the professor will be just behind the door – carrying a large mallet. Baby Face tries a cautious creep, but just as he extends his hands for the target bottle, Rat-Face emerges to whack both of his hands hard with the mallet. While Baby Face tends to his throbbing hands, the Professor demonstrates the proper method of approach, standing with his back turned to the bottle, as if ignoring it, then whisking it away in a blur. The Professor boasts that “Rat-Face is faster than the eye.” Baby Face sees an opportunity for escape, and smacks the bottom of the milk bottle, ejecting the lactose right into the rat’s eyes. Then, he uses the Professor’s mallet to conk him on the head, leaving a lump under the professor’s hat. Baby Face turns to leave, but is grabbed up by the tail, as the rat observes in appreciation of the kid’s moxie, “I think I’m gonna like you…but take it easy on the rough stuff!” Next comes a lesson in pickpocketing. Baby Face is again aghast at such criminal ideas, disappointing the professor. “There you go again, just when I thought we was gonna be pals.” He nevertheless continues Baby Face’s training, instructing him to take a watch, and hide it in one of his pockets when the rat isn’t looking, so he can demonstrate how to pilfer it. While the rat’s eyes are closed, Beby Face gets another idea to outfox the Professor. Spying a mousetrap, he neatly removes the cheese for himself, then places the unsprung trap into his pocket instead of the watch. Rat-Face dips his hand in, and SNAP! As Rat-Face struggles to get the gadget off his hand, he only succeeds in flipping the trap onto his nose. Baby Face offers to help, briefly opening the trap, but lets it shut again upon the rat schnozzola, emphasizing again that crime doesn’t pay. The professor has had it with this pupil’s double-crosses, and lunges for him to tear him limb from limb. The two chase around the cellar, until Baby Face spots an old fashioned phone on the wall. He hastily rings up police headquarters, but is unable to get all the words out for his distress call before Rat-Face makes another pass. “Hold the phone”, says Baby Face, taking another lap around the room. He tries again to complete the call, but pauses in the message again for another run. Finally, he yanks the phone completely off the wall, and carries ot with him for a third run around the room. Thinking he has given the police all the details, he places the phone back on the wall – but by the next pass, the phone rings for him. The chase pauses as Baby Face answers the call. It is the police again, asking for the one key piece of information Baby Face omitted. “Uh, what is the address here?” Baby Face asks the rat. Reflexively, the rat volunteers, “329 Bunco Street”, then realizes he’s blurted out something he shouldn’t have told. Baby Face repeats the info to the cops, and hangs up. The chase is on again, but as Rat-Face approaches the doorway of the room (where a wanted poster is hung proudly on a nearby wall, indicating there is a $5,000 reward for his capture), the door is suddenly pushed open bu a cop, causing Rat Face to run face first into the door, knocking himself cold. The officer sizes up the situation, with unconscious rat and smiling, proud mouse, and takes Rat-Face into custody, not without some police brutality, repeatedly clubbing Rat-Face although he is motionless, while stating, “Resisting an officer!” The final scene takes place back at Baby Face’s home, where the cop tells Mom that junior captured public enemy number one, and is a “brave little man”. Mom holds Baby Face, planting a kiss upon him, while stating, “This is for being a brave little man” – then, she takes Baby Face across her knee. “And this is for crossing the railroad tracks!”, she says, as she paddy-whacks her son’s rear end but good.

The rat directs Baby Face to follow him over to a door frame without a wall, and a bottle of milk. First lesson is to swipe the milk without the owner catching you. Baby Face gently protests at the idea, insisting that crime doesn’t pay. “Quiet”, shouts the rat, slapping the mouse across the face with the back of his glove, “Don’t talk back to the teacher.” The rat cautions Baby Face that he must perform the task quickly, as the professor will be just behind the door – carrying a large mallet. Baby Face tries a cautious creep, but just as he extends his hands for the target bottle, Rat-Face emerges to whack both of his hands hard with the mallet. While Baby Face tends to his throbbing hands, the Professor demonstrates the proper method of approach, standing with his back turned to the bottle, as if ignoring it, then whisking it away in a blur. The Professor boasts that “Rat-Face is faster than the eye.” Baby Face sees an opportunity for escape, and smacks the bottom of the milk bottle, ejecting the lactose right into the rat’s eyes. Then, he uses the Professor’s mallet to conk him on the head, leaving a lump under the professor’s hat. Baby Face turns to leave, but is grabbed up by the tail, as the rat observes in appreciation of the kid’s moxie, “I think I’m gonna like you…but take it easy on the rough stuff!” Next comes a lesson in pickpocketing. Baby Face is again aghast at such criminal ideas, disappointing the professor. “There you go again, just when I thought we was gonna be pals.” He nevertheless continues Baby Face’s training, instructing him to take a watch, and hide it in one of his pockets when the rat isn’t looking, so he can demonstrate how to pilfer it. While the rat’s eyes are closed, Beby Face gets another idea to outfox the Professor. Spying a mousetrap, he neatly removes the cheese for himself, then places the unsprung trap into his pocket instead of the watch. Rat-Face dips his hand in, and SNAP! As Rat-Face struggles to get the gadget off his hand, he only succeeds in flipping the trap onto his nose. Baby Face offers to help, briefly opening the trap, but lets it shut again upon the rat schnozzola, emphasizing again that crime doesn’t pay. The professor has had it with this pupil’s double-crosses, and lunges for him to tear him limb from limb. The two chase around the cellar, until Baby Face spots an old fashioned phone on the wall. He hastily rings up police headquarters, but is unable to get all the words out for his distress call before Rat-Face makes another pass. “Hold the phone”, says Baby Face, taking another lap around the room. He tries again to complete the call, but pauses in the message again for another run. Finally, he yanks the phone completely off the wall, and carries ot with him for a third run around the room. Thinking he has given the police all the details, he places the phone back on the wall – but by the next pass, the phone rings for him. The chase pauses as Baby Face answers the call. It is the police again, asking for the one key piece of information Baby Face omitted. “Uh, what is the address here?” Baby Face asks the rat. Reflexively, the rat volunteers, “329 Bunco Street”, then realizes he’s blurted out something he shouldn’t have told. Baby Face repeats the info to the cops, and hangs up. The chase is on again, but as Rat-Face approaches the doorway of the room (where a wanted poster is hung proudly on a nearby wall, indicating there is a $5,000 reward for his capture), the door is suddenly pushed open bu a cop, causing Rat Face to run face first into the door, knocking himself cold. The officer sizes up the situation, with unconscious rat and smiling, proud mouse, and takes Rat-Face into custody, not without some police brutality, repeatedly clubbing Rat-Face although he is motionless, while stating, “Resisting an officer!” The final scene takes place back at Baby Face’s home, where the cop tells Mom that junior captured public enemy number one, and is a “brave little man”. Mom holds Baby Face, planting a kiss upon him, while stating, “This is for being a brave little man” – then, she takes Baby Face across her knee. “And this is for crossing the railroad tracks!”, she says, as she paddy-whacks her son’s rear end but good.

Count Me Out (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Egghead), 12/17/38 – Ben Hardaway/Cal Dalton, dir.), may mark the first time a character attempted to learn a trade through a correspondence course. Down on the farm, Egghead reads an ad for the Acme Correspondence School of Boxing, which challenges its readers, “Are you a man or a mouse? Fight your way to success. Mail us $1.00 and be the next champ.” Egghead has a special mailbox, marked as his private air mail. Opening it up, he pulls out a wind-up rubber band powered toy airplane, attaches his dollar to it, and sends it on its way. In less than a split second, a postal wagon is delivering him a large package, the elderly driver complaining that he would have been there sooner, but the bridge was out entirely. One dollar before inflation seems to have bought a lot in those days, as the package contains punching bags, gloves, dumbbells, and various other equipment. In actuality, just the phonograph records included in the set to provide instruction would have generally cost 75 cents to a dollar apiece in those days, so the advertised price is impossibly low. Egghead puts on the first record for lesson one. Following instructions is difficult – such as when the recorded announcer (Mel Blanc in his normal speaking voice), after telling Egghead to take a deep breath, pauses in his narration because someone is calling him on the phone at the recording studio, leaving Egghead turning blue from holding his breath. Instructions on how to jab increase in pace to chipmunk-voiced speed, leaving Egghead panting in exhaustion. “Stick in your tongue”, says the announcer, “There’s people looking at you!” Lesson four introduces a contraption consisting of five boxing gloves fastened to mechanical jointed arms, mounted in a wall panel, each glove labelled for delivering such punches as “left hook”, “upper cut”, etc. A step upon a switch installed in the floor activates the gloves, to allow Egghead to practice dodging a rapid-fire succession of blows. Egghead completes the process unscathed, at which the phonograph record announces he’s completed his instruction, and another mechanical hand emerges from the phonograph to hand him a diploma. Happy Egghead darts into the closet, emerging with satchels packed for a trip to the big city, and in his best traveling clothes. He looks at his physique in the mirror, and observes aloud at his reflection, “I can’t get over it. I’m a professional prize fighter.” He struts forward, ready to take on the world. However, his foot steps on the switch which activates the punching machine, and he is knocked to the floor by the blow of one of the gloves, in a seeming knockout punch.

Count Me Out (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Egghead), 12/17/38 – Ben Hardaway/Cal Dalton, dir.), may mark the first time a character attempted to learn a trade through a correspondence course. Down on the farm, Egghead reads an ad for the Acme Correspondence School of Boxing, which challenges its readers, “Are you a man or a mouse? Fight your way to success. Mail us $1.00 and be the next champ.” Egghead has a special mailbox, marked as his private air mail. Opening it up, he pulls out a wind-up rubber band powered toy airplane, attaches his dollar to it, and sends it on its way. In less than a split second, a postal wagon is delivering him a large package, the elderly driver complaining that he would have been there sooner, but the bridge was out entirely. One dollar before inflation seems to have bought a lot in those days, as the package contains punching bags, gloves, dumbbells, and various other equipment. In actuality, just the phonograph records included in the set to provide instruction would have generally cost 75 cents to a dollar apiece in those days, so the advertised price is impossibly low. Egghead puts on the first record for lesson one. Following instructions is difficult – such as when the recorded announcer (Mel Blanc in his normal speaking voice), after telling Egghead to take a deep breath, pauses in his narration because someone is calling him on the phone at the recording studio, leaving Egghead turning blue from holding his breath. Instructions on how to jab increase in pace to chipmunk-voiced speed, leaving Egghead panting in exhaustion. “Stick in your tongue”, says the announcer, “There’s people looking at you!” Lesson four introduces a contraption consisting of five boxing gloves fastened to mechanical jointed arms, mounted in a wall panel, each glove labelled for delivering such punches as “left hook”, “upper cut”, etc. A step upon a switch installed in the floor activates the gloves, to allow Egghead to practice dodging a rapid-fire succession of blows. Egghead completes the process unscathed, at which the phonograph record announces he’s completed his instruction, and another mechanical hand emerges from the phonograph to hand him a diploma. Happy Egghead darts into the closet, emerging with satchels packed for a trip to the big city, and in his best traveling clothes. He looks at his physique in the mirror, and observes aloud at his reflection, “I can’t get over it. I’m a professional prize fighter.” He struts forward, ready to take on the world. However, his foot steps on the switch which activates the punching machine, and he is knocked to the floor by the blow of one of the gloves, in a seeming knockout punch.

The next thing we know, the scene dissolves to an arena marquee, advertising tonight’s event – a championship match between Egghead and the reigning champion, Biff Stew. Inside, a jovial, rotund referee introduces Biff (who ensures nobody will miss his holding of chapionship status by advertising his name and title in scrolling lights (like a Times Square sign) on the back of his cape. The referee introduces Egghead, and nearly dies laughing, with under the breath comments of “What a physique. You can have him!” The voice of the referee appears to be the same infectious laugh heard from the Hippopotamus In the audience of Egghead’s “Hamateur Night”, and from the Walrus in “The Penguin Parade” – leading to the conclusion that, despite the fact that this is one of the rare times that Egghead, a character designed by Tex Avery, was directed by someone else, Avery himself was not far away from the production – providing the voice of the referee. Perhaps Avery’s unit created at least portions of the storyboard, and might even have pre-recorded portions of the soundtrack, before the project was rerouted to Hardaway and Dalton, possibly accounting for Avery’s presence on the track. The laughter overwhelms the referee to such extent, that he topples over the ropes and out of the ring. A timekeeper begins the match with a knee-reflex kick of the starting bell. Egghead’s correspondence course, even though his formal instruction is complete, includes additional records to provide the advice of a coach in Egghead’s corner – thus, Egghead has brought his old phonograph into the ring. “There goes the bell. Fly into him”, instructs the record. Egghead runs a few quick laps around his opponent, attemting to weaken him with a circle of blows. Unphased, Biff blows upon the thumb of one boxing glove, inflating the glove to expand and unroll like a burthday party favor, socking Egghead in the face. He repeats the activity, but in a fakeout – instead of waiting for the glove to unroll, he sneaks in a blow with his other fist on Egghead’s dome. A jack-hammer punch, use of Eddhead’s cranium as a punching bag, and a sound upper cut, send Egghead flying across the ring, back into his corner. “Come come”, says the record announcer, “You’re fighting for dear old Acme.” Amid the nonsense double talk of a ringside sportscaster (including such random phrases as “Nice work if you can get it”, “Susie Q”, and “If you need money or car, paid for or not…”), Egghead is lost in a cartoon fight cloud. When the dust clears, Egghead stumbles around in search of his corner, and winds up sitting on Biff’s lap, assuming a voice that is an impression of ventrilquist dummy Charlie McCarthy – “Fancy meeting you here. It’s a small world.” The bell sounds again, and Biff delivers a blow, launching Egghead back to the opposite corner, directly atop his phonograph, which is smashed from the impact. “I don’t wanna fight anymore”, he whimpers. But Biff won’t let him climb through the ropes, saying, “Where do ya think you’re goin’?” A right cross sends Egghead into the ropes, telescoping his head almost into the camera lens, then throws him back into the ring like an elastic band, straight into Biff’s belly. Both fighters wind up down on the mat, with Biff on top. Egghead takes a strong bite on Biff’s lower leg, sending the champ jumping into the air. He falls back so hard upon the canvas, he knocks a hole in the flooring below it, pulling in the mat with him, and leaving Egghead scrambling to avoid falling into the hole. At this point, as the music score plays “Let That Be a Lesson To You”, the scene dissolves back to Egghead’s home, where Egghead is in the same place where he was knocked out by the punching machine. The fight was all a dream. Disgusted, Egghead takes up the ponograph, dumbbells, punching bag and other materials, and dumps them out the window into the trash. “I’m through with this”. Egghead vows. However, he has left one item undisposed of – the punching machine. Accidentally stepping on the floor switch again, Egghead is hit by the same upper cut, and is once again down for the count for the iris out.

The next thing we know, the scene dissolves to an arena marquee, advertising tonight’s event – a championship match between Egghead and the reigning champion, Biff Stew. Inside, a jovial, rotund referee introduces Biff (who ensures nobody will miss his holding of chapionship status by advertising his name and title in scrolling lights (like a Times Square sign) on the back of his cape. The referee introduces Egghead, and nearly dies laughing, with under the breath comments of “What a physique. You can have him!” The voice of the referee appears to be the same infectious laugh heard from the Hippopotamus In the audience of Egghead’s “Hamateur Night”, and from the Walrus in “The Penguin Parade” – leading to the conclusion that, despite the fact that this is one of the rare times that Egghead, a character designed by Tex Avery, was directed by someone else, Avery himself was not far away from the production – providing the voice of the referee. Perhaps Avery’s unit created at least portions of the storyboard, and might even have pre-recorded portions of the soundtrack, before the project was rerouted to Hardaway and Dalton, possibly accounting for Avery’s presence on the track. The laughter overwhelms the referee to such extent, that he topples over the ropes and out of the ring. A timekeeper begins the match with a knee-reflex kick of the starting bell. Egghead’s correspondence course, even though his formal instruction is complete, includes additional records to provide the advice of a coach in Egghead’s corner – thus, Egghead has brought his old phonograph into the ring. “There goes the bell. Fly into him”, instructs the record. Egghead runs a few quick laps around his opponent, attemting to weaken him with a circle of blows. Unphased, Biff blows upon the thumb of one boxing glove, inflating the glove to expand and unroll like a burthday party favor, socking Egghead in the face. He repeats the activity, but in a fakeout – instead of waiting for the glove to unroll, he sneaks in a blow with his other fist on Egghead’s dome. A jack-hammer punch, use of Eddhead’s cranium as a punching bag, and a sound upper cut, send Egghead flying across the ring, back into his corner. “Come come”, says the record announcer, “You’re fighting for dear old Acme.” Amid the nonsense double talk of a ringside sportscaster (including such random phrases as “Nice work if you can get it”, “Susie Q”, and “If you need money or car, paid for or not…”), Egghead is lost in a cartoon fight cloud. When the dust clears, Egghead stumbles around in search of his corner, and winds up sitting on Biff’s lap, assuming a voice that is an impression of ventrilquist dummy Charlie McCarthy – “Fancy meeting you here. It’s a small world.” The bell sounds again, and Biff delivers a blow, launching Egghead back to the opposite corner, directly atop his phonograph, which is smashed from the impact. “I don’t wanna fight anymore”, he whimpers. But Biff won’t let him climb through the ropes, saying, “Where do ya think you’re goin’?” A right cross sends Egghead into the ropes, telescoping his head almost into the camera lens, then throws him back into the ring like an elastic band, straight into Biff’s belly. Both fighters wind up down on the mat, with Biff on top. Egghead takes a strong bite on Biff’s lower leg, sending the champ jumping into the air. He falls back so hard upon the canvas, he knocks a hole in the flooring below it, pulling in the mat with him, and leaving Egghead scrambling to avoid falling into the hole. At this point, as the music score plays “Let That Be a Lesson To You”, the scene dissolves back to Egghead’s home, where Egghead is in the same place where he was knocked out by the punching machine. The fight was all a dream. Disgusted, Egghead takes up the ponograph, dumbbells, punching bag and other materials, and dumps them out the window into the trash. “I’m through with this”. Egghead vows. However, he has left one item undisposed of – the punching machine. Accidentally stepping on the floor switch again, Egghead is hit by the same upper cut, and is once again down for the count for the iris out.

Small Fry (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classics, 4/22/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Orestes Calpini, amin.), actually has very little content to do with schooling, but deserves honotable mention, as the sequel to 1936’s “Educated Fish”, previously discussed in this series. Two principal characters fro the original appear, although their names are changed (to protect the innocent?) Our little tough orange fish and would-be delinquent, Tommy Cod, merely acquires the nicknames of “Junior” and “Small Fry”. His species even changes, as instead of a cod, his mother is referred to as “Mrs. Catfish”. As previously referenced, the formerly anonymous grade school teacher-fish is now known by name as Miss Pickerel.

Small Fry (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classics, 4/22/39 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/Orestes Calpini, amin.), actually has very little content to do with schooling, but deserves honotable mention, as the sequel to 1936’s “Educated Fish”, previously discussed in this series. Two principal characters fro the original appear, although their names are changed (to protect the innocent?) Our little tough orange fish and would-be delinquent, Tommy Cod, merely acquires the nicknames of “Junior” and “Small Fry”. His species even changes, as instead of a cod, his mother is referred to as “Mrs. Catfish”. As previously referenced, the formerly anonymous grade school teacher-fish is now known by name as Miss Pickerel.

The film opens as we again travel below the water’s surface, to the ale barrel that serves as the schoolhouse for the local fish children. This time, the school day is just concluding, and all the minnows, guppies, sardines and whatnot swim out the doors and windows of the structure to head home. But there’s been one absentee for the day, and Miss Pickerel is doing something about it. As she locks up the door of the school (that is to say, turns a key to seal up the top of a sardine can that serves as the barrel’s entrance), she hands one of her students a note to deliver to Mrs. Catfish. Knowing what that means, the student begins to chant musically as he heads for the catfish residence, “Junior’s gonna get it”. The note is delivered to an old teapot which serves as the Catfish home. Mrs. Catfish reads: “Your son Junior was absent from school today. Was it hookey, or did he get hooked?” Having no idea where her boy is, Mrs. Catfish frets and worries herself silly as to when Junior will return home. But Junior is in no immediate danger – except of being embarrassed by reason of his conduct. He is hanging out at the local underwater pool parlor (that moisture must be murder on those felt table coverings), trying his hand at the game, to be like the big boys that otherwise inhabit the place. His shirt is hooked by the back end of a pool cue held by a player at the next table, disrupting the other player’s shot. “Hey, what do you think you are, a big shot?”, the peeved patron comments to Junior, and retaliates by using Junior as the pool cue to knock in all the balls at Junior’s table with one shot. On one wall of the parlor, a hammerhead shark nails up a large poster, announcing there will be a meeting tonight at the parlor of the Big Fry Club – members only allowed. Seemingly all the larger fish in the parlor are among the membership, and clamor around the sign, announcing their intention to be there. Junior sneaks between their fins to “get a gander” at the poster, them, with a slight hesitation, gets up nerve to ask the large fish if he can be a member. One fish gives a wink to another, seeing an opportunity for fun – and the fish invite Junior to come around tonight to apply for membership. Junior is excited, but tries to hide his enthusiasm with a show of adult-style assuredness. On his way out, he picks up a fallen cigarette butt, and attempts an inhale from it, instantly breaking into a coughing jag. “Must be catchin’ cold or somethin”“, he covers, amidst the loud laughter of the membership, and retains his swagger as he saunters out of the hall.

Much of the middle of the film is occupied by a full rendition of Hoagy Camichael’s immortal song from which the cartoon derives its title and most of its score – perhaps best known to record collectors from the spirited duet recorded by Bing Crosby and Johnny Mercer for Decca. With no attmpt at apology, Juniot shows up at home, and gets a musical bawling out by his Mother, although, being a conscientious parent, she does not send Junior to bed without supper, but permits him to digest a hearty sandwich four times his height. But after dinner, his mother’s words bouncing off him like water off a duck’s back, Junior attempts to head out again, to attend the special meeting. Mama will have none of this, and sends Junior to his room. But as we’ve seen in the previous cartoon, rooms are no obstacles to Junior, given the underwater nature of his habitat, and he merely swims up and out through the window. Arriving at the pool hall, he is admitted for a special initiation. At the rear of the hall, previously undisclosed from out earlier views, is the entrance to a secret grotto. A senior club member ties a blindfold around Junior’s eyes, gives him a cigarette (perhaps in the same manner as a last smoke to a person about to face a firing squad), and pushes him into the mouth of the grotto. The memberhip peeps in the grotto’s opening, blocking any hope of retreat, and an eel swims past Junior, spinning him and causing the blindfold to fall off. The grotto’s inner cave is in pitch darkness, and Junior is left to explore the cave’s interior alone. In a surreal reprise of the title song, the membership taunts Junior, while a collection of denizens of the deep which the membership seem to have amassed as a menagerie send waves of panic and shock through Junior. The ceatures are largely depicted in the form of colored outlines only, as if seen in neon provided only by their own internal luminescence. Junior is ultimately surrounded, and several creatures transform into one large one, whose tongue beckons Junior to enter its humongous mouth. That’s all that Junior can take, and, like a bullet, he darts between and through the membership at the cave door, and out of the hall, making a beeline for home amidst the deriding laughter of the crowd at his failure. He runs straight into the arms of Mommy, again promising that he’ll be a good little boy and never do it again. In a final line of the song, which is all the funnier because of its setting underwater, Mama sings, “You got your feet all soaking wet. You’ll be the death of me yet. Oh, me, oh, my, Small Fry!”

Much of the middle of the film is occupied by a full rendition of Hoagy Camichael’s immortal song from which the cartoon derives its title and most of its score – perhaps best known to record collectors from the spirited duet recorded by Bing Crosby and Johnny Mercer for Decca. With no attmpt at apology, Juniot shows up at home, and gets a musical bawling out by his Mother, although, being a conscientious parent, she does not send Junior to bed without supper, but permits him to digest a hearty sandwich four times his height. But after dinner, his mother’s words bouncing off him like water off a duck’s back, Junior attempts to head out again, to attend the special meeting. Mama will have none of this, and sends Junior to his room. But as we’ve seen in the previous cartoon, rooms are no obstacles to Junior, given the underwater nature of his habitat, and he merely swims up and out through the window. Arriving at the pool hall, he is admitted for a special initiation. At the rear of the hall, previously undisclosed from out earlier views, is the entrance to a secret grotto. A senior club member ties a blindfold around Junior’s eyes, gives him a cigarette (perhaps in the same manner as a last smoke to a person about to face a firing squad), and pushes him into the mouth of the grotto. The memberhip peeps in the grotto’s opening, blocking any hope of retreat, and an eel swims past Junior, spinning him and causing the blindfold to fall off. The grotto’s inner cave is in pitch darkness, and Junior is left to explore the cave’s interior alone. In a surreal reprise of the title song, the membership taunts Junior, while a collection of denizens of the deep which the membership seem to have amassed as a menagerie send waves of panic and shock through Junior. The ceatures are largely depicted in the form of colored outlines only, as if seen in neon provided only by their own internal luminescence. Junior is ultimately surrounded, and several creatures transform into one large one, whose tongue beckons Junior to enter its humongous mouth. That’s all that Junior can take, and, like a bullet, he darts between and through the membership at the cave door, and out of the hall, making a beeline for home amidst the deriding laughter of the crowd at his failure. He runs straight into the arms of Mommy, again promising that he’ll be a good little boy and never do it again. In a final line of the song, which is all the funnier because of its setting underwater, Mama sings, “You got your feet all soaking wet. You’ll be the death of me yet. Oh, me, oh, my, Small Fry!”

Fresh Fish (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 11/4/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), is one of those typical but well made Avery spot gag cartoons about ocean life, framed around a running gag of a professor’s bathysphere search for the elusive whim-wham whistling shark. For our purposes, its relevance is for another underwater classroom experience with a “school” of fish. As usual, the subject for today’s lesson is how not to get the hook. The professor stresses that the correct approach to the hook is from the underside, providing demonstrations with a real hook dangling on a line just above the open-air (er, that is, water) classroom. Prefacing each maneuver with the words, “Like this”, the professor demonstrates a forward nibble at the hook’s bottom cutve, and a “double-twist tail angle”, making the same underside approach while swimming upside down. “But by all means,” the professor cautions, “never approach the hook straight on, like this.” Carrying the zealousness of his demonstrative approach too far, the professor bites squarely upon the hook’s point – and is immediately yanked upward by the line and out of the scene. A moment later, the hook descends into the water again, with a paper note hanging from it, reading “Class dismissed.” The students, with no regard for their teacher’s safety or well being, cheer happily as they exit their shell desks for the freedom of the remainder of the day. Hope they find a substitute teacher by morning.

Fresh Fish (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 11/4/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), is one of those typical but well made Avery spot gag cartoons about ocean life, framed around a running gag of a professor’s bathysphere search for the elusive whim-wham whistling shark. For our purposes, its relevance is for another underwater classroom experience with a “school” of fish. As usual, the subject for today’s lesson is how not to get the hook. The professor stresses that the correct approach to the hook is from the underside, providing demonstrations with a real hook dangling on a line just above the open-air (er, that is, water) classroom. Prefacing each maneuver with the words, “Like this”, the professor demonstrates a forward nibble at the hook’s bottom cutve, and a “double-twist tail angle”, making the same underside approach while swimming upside down. “But by all means,” the professor cautions, “never approach the hook straight on, like this.” Carrying the zealousness of his demonstrative approach too far, the professor bites squarely upon the hook’s point – and is immediately yanked upward by the line and out of the scene. A moment later, the hook descends into the water again, with a paper note hanging from it, reading “Class dismissed.” The students, with no regard for their teacher’s safety or well being, cheer happily as they exit their shell desks for the freedom of the remainder of the day. Hope they find a substitute teacher by morning.

Fagin’s Freshman (Warner Brothers, Merrie Melodies, 11/18/39 – Ben Hardaway/Cal Dalton, dir.), follows in the footsteps of “The Disobedient Mouse”, with another crime school. this time for cats instead of mice. Not only taking a leaf from the studio’s own feature ‘Crime School” discussed above, the title suggests a nodding reference to another famous teacher of junior delinquents, Fagin, the leader of a band of pickpockets in Charles Disckens’ legendary story, “Oliver Twist”. There is, however, no particular reference to an “artful dodger”, the hero of our story being anything but artful. The film centers around a kitten named Ambrose, who is fed up with the sissy stuff that his Mother and sisters call activities (gathering around a pumper organ, and singing endless refrains of “Three Little Kittens”). “Kimdergarden stuff”, Ambrose tells the audience. He disrupts the proceedings by turning on the radio to a broadcast of “Gang Busters”, drowning out the singing with the sounds of machine gun fire and wailing police sirens. Mama drags Ambrose by the ear upstairs and to his room, to spend the night without supper until he learns to stop thinking of nothing but crime and gunplay. After some bedside grumbling, Ambrose nods off to sleep – and is immediately seen in transparent “dream” form rising from the bed, sauntering across the room, then being magically transported in his dream form to a run-down neighborhood on the bad side of town. Passing a building with numerous boards hanging out of place from one nail, he spots a sign on the wall. “Boys Wanted. No experience ncessary. Earn while you learn.” Looks appealing enough, so Ambrose knocks on the door. A large burly cat, in a derby and smoking a cigar, answers the door, after peering out two peepholes – one high on the door for adults, one low on the door for kids. He is Fagin, the proprietor of the establishment, who invites the newcomer in.

Fagin’s Freshman (Warner Brothers, Merrie Melodies, 11/18/39 – Ben Hardaway/Cal Dalton, dir.), follows in the footsteps of “The Disobedient Mouse”, with another crime school. this time for cats instead of mice. Not only taking a leaf from the studio’s own feature ‘Crime School” discussed above, the title suggests a nodding reference to another famous teacher of junior delinquents, Fagin, the leader of a band of pickpockets in Charles Disckens’ legendary story, “Oliver Twist”. There is, however, no particular reference to an “artful dodger”, the hero of our story being anything but artful. The film centers around a kitten named Ambrose, who is fed up with the sissy stuff that his Mother and sisters call activities (gathering around a pumper organ, and singing endless refrains of “Three Little Kittens”). “Kimdergarden stuff”, Ambrose tells the audience. He disrupts the proceedings by turning on the radio to a broadcast of “Gang Busters”, drowning out the singing with the sounds of machine gun fire and wailing police sirens. Mama drags Ambrose by the ear upstairs and to his room, to spend the night without supper until he learns to stop thinking of nothing but crime and gunplay. After some bedside grumbling, Ambrose nods off to sleep – and is immediately seen in transparent “dream” form rising from the bed, sauntering across the room, then being magically transported in his dream form to a run-down neighborhood on the bad side of town. Passing a building with numerous boards hanging out of place from one nail, he spots a sign on the wall. “Boys Wanted. No experience ncessary. Earn while you learn.” Looks appealing enough, so Ambrose knocks on the door. A large burly cat, in a derby and smoking a cigar, answers the door, after peering out two peepholes – one high on the door for adults, one low on the door for kids. He is Fagin, the proprietor of the establishment, who invites the newcomer in.

Ambrose introduces himself, claiming that despite his real name, his friends call him Blackie. He is led into a classroom where the students are enjoying recess by shooting craps. Ambrose is surprised to learn he must go to school as part of this new position. Fagin reminds him that one “can’t get noplaces nowadays without no education.” He points to a series of pictures on the wall, showiing how his former graduates are in demand. The gallery includes wanted posters for an arsonist (Fat Burns, alias Flash Jordon, alias Smoky Snyder, alias Holocaust Harry), a confidence man (Fibber McKee – a play on radio’s “Fibber McGee”), and a group shot of the class of 1920, all in prison stripes, but holding pardons. “Ya mean you teach little boys to be criminals?” asks shocked Ambrose. Fagin winces at the thought, claiming he only teaches them the basic principles, sends them out as refined gentlement, then – – well, gold is where you find it. The class performs a production number set to the tune, “We’re Working Our Way Through College” but with new lyrics, accompanying efforts at pickpocketing, safe cracking, and avoinding spending time in the penitentiary. We do not, however, get a chance to see Fagin’s teaching methods, as a knock on the door turns our to be an officer of the law. A squad of officers attempts a siege of the place, while Ambrose has something of a reality crisis at the goings on. “Are they real policemen?”, he asks. “Well if they ain’t, they’re a reasonable facsimile”, answers Fagin. “Are they shooting real bullets?”, Ambrose asks again, as a hole is shot through Fagin’s hat. “That wasn’t done by no moth”, reples Fagin again. The cops are bumbling and inept, however, as the siege goes on, failing to gain entry when a battering ram penetrates the door but leaves the cops flattened against the door’s outside. From trash barrels, behind fences and in alleyways they try to keep up their fire while dodging the bullets of Fagin’s pistol and a machine gun operated by one of Ambrose’s classmates. A telephone call rings Fagin’s phone, and Fagin tells the cops from his window to pipe down with their gunfire so he can hear the call. The caller is the wife of one of the cops, who Fagin calls out to from the window, instructing him that the little woman wants him to pick up a pound of butter on the way home. The police finally bring in a machine gun of their own. A spray of bulets hits the wall just behind Ambrose, and follows him as he runs across the room. He attempts to open a door, but more bullets shoot into the door the words, “No No”. Ambrose is finally forced to jump out of an upper story window, taking the window curtains with him. He falls through the air helplessly, only to awaken tangled up in his bedsheets. He’s had enough of this dream, and races dowestairs to join his sisters and Mom in the never-ending verses of the “Kittens” song, a halo appearing above Ambrose’s head as a reformed angel, for the iris out. This film possibly ranks among the least known or remembered color Merrie Melodies, and seemed to be hardly ever shown on TV (possibly because of its unsavory subject matter – a bit too heavy for today’s kids or for mothers’ groups).

Ambrose introduces himself, claiming that despite his real name, his friends call him Blackie. He is led into a classroom where the students are enjoying recess by shooting craps. Ambrose is surprised to learn he must go to school as part of this new position. Fagin reminds him that one “can’t get noplaces nowadays without no education.” He points to a series of pictures on the wall, showiing how his former graduates are in demand. The gallery includes wanted posters for an arsonist (Fat Burns, alias Flash Jordon, alias Smoky Snyder, alias Holocaust Harry), a confidence man (Fibber McKee – a play on radio’s “Fibber McGee”), and a group shot of the class of 1920, all in prison stripes, but holding pardons. “Ya mean you teach little boys to be criminals?” asks shocked Ambrose. Fagin winces at the thought, claiming he only teaches them the basic principles, sends them out as refined gentlement, then – – well, gold is where you find it. The class performs a production number set to the tune, “We’re Working Our Way Through College” but with new lyrics, accompanying efforts at pickpocketing, safe cracking, and avoinding spending time in the penitentiary. We do not, however, get a chance to see Fagin’s teaching methods, as a knock on the door turns our to be an officer of the law. A squad of officers attempts a siege of the place, while Ambrose has something of a reality crisis at the goings on. “Are they real policemen?”, he asks. “Well if they ain’t, they’re a reasonable facsimile”, answers Fagin. “Are they shooting real bullets?”, Ambrose asks again, as a hole is shot through Fagin’s hat. “That wasn’t done by no moth”, reples Fagin again. The cops are bumbling and inept, however, as the siege goes on, failing to gain entry when a battering ram penetrates the door but leaves the cops flattened against the door’s outside. From trash barrels, behind fences and in alleyways they try to keep up their fire while dodging the bullets of Fagin’s pistol and a machine gun operated by one of Ambrose’s classmates. A telephone call rings Fagin’s phone, and Fagin tells the cops from his window to pipe down with their gunfire so he can hear the call. The caller is the wife of one of the cops, who Fagin calls out to from the window, instructing him that the little woman wants him to pick up a pound of butter on the way home. The police finally bring in a machine gun of their own. A spray of bulets hits the wall just behind Ambrose, and follows him as he runs across the room. He attempts to open a door, but more bullets shoot into the door the words, “No No”. Ambrose is finally forced to jump out of an upper story window, taking the window curtains with him. He falls through the air helplessly, only to awaken tangled up in his bedsheets. He’s had enough of this dream, and races dowestairs to join his sisters and Mom in the never-ending verses of the “Kittens” song, a halo appearing above Ambrose’s head as a reformed angel, for the iris out. This film possibly ranks among the least known or remembered color Merrie Melodies, and seemed to be hardly ever shown on TV (possibly because of its unsavory subject matter – a bit too heavy for today’s kids or for mothers’ groups).

Homework for next week is to prepare to enter the 1940’s – and to meet that arch nemesis of all young boys’ nightmares – the truant officer.